It was a Barolo producer who introduced me to the vineyards of Alta Langa. On a sunny September morning this past fall, Sergio Germano, of Serralunga’s Ettore Germano, drove as we climbed our way along winding roads toward the village of Cigliè, passing grain fields, hazelnut trees and a man with a shotgun. “Probably hunting boar,” said Germano, who fences his Alta Langa vineyards to keep them out. As we crested each hill, the Maritime Alps rose into view toward the southwest. “From here we are 45 minutes to the closest ski slope and one hour to the Ligurian Sea,” he told me.

The Alta Langa is radically different from the manicured monoculture of Barolo. This vast region, which attained DOCG status 12 years ago, skirts the southern edges of Barolo and Barbaresco, extending across the provinces of Asti, Alessandria and Cuneo. In contrast to Alto Piemonte, the area north of Barolo where a range of DOCs and DOCGs specialize in red wines from nebbiolo, the Alta Langa denomination was created exclusively for bottle-fermented sparkling wines from pinot noir and chardonnay.

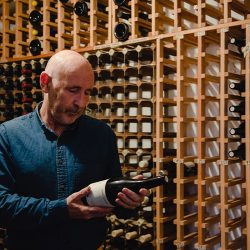

Germano was an early supporter of Alta Langa, and now owns 25 acres of vines, with plans to plant seven more in the coming years. His vineyard is surrounded by scrubby herbs, the white, limestone-laden soils visible between rows that run along steep slopes, the Tanaro River streaming far below. Nets protect the clusters from the frequent hailstorms on these high, exposed ridges. Langa is a local variation on Langhe, the area to the south and east of the Tanaro River that includes Barolo and Barbaresco, he explains, adding, “Alta Langa reminds me of Serralunga 50 years ago, in my childhood. There were more different kinds of crops, colder winters, more snow.”

Alta Langa’s cooler climes have drawn other Barolo producers, such as Fontanafredda, one of the original seven members behind Spumante Metodo Classico in Piemonte, a project initiated in 1990 to study the soils and expositions of the region and identify the best areas to grow pinot noir and chardonnay for sparkling wines.

One of the Spumante Piemonte project’s initial goals was to invest in what had become an impoverished region and convince small growers not to abandon their land. In addition to the 26 acres Fontanafredda now owns in the Alta Langa, their technical team works with 34 growers who farm another 123 acres. “It was important that the growers become the first architects of this area,” says Roberto Bruno, the estate’s commercial director. Since 2014, they have ramped up production of Alta Langa wines from 40,000 bottles to 350,000.

Borgogno, another Barolo producer that, like Fontanafredda, is owned by Oscar Farinetti, recently acquired 49 acres of land at 2,800 feet a.s.l., one of the highest points of Alta Langa. They’re gradually planting vines and building a new winery, due to be finished in 2027, with the first wines slated for release in 2030.

Despite that kind of growth, Alta Langa remains a nascent region, producing just three million bottles a year. To put that in context with their Italian competitors, Franciacorta now makes about 20 million bottles a year, and Trentodoc produces 13 million. Even those numbers pale in comparison to the more than 326 million bottles coming out of Champagne. The Consorzio carefully controls the region’s expansion—the DOCG requires that vineyards must be planted on hillsides with calcareous-clay soils at a minimum elevation of 820 feet a.s.l. So far, there are only 934 acres of vines, but the Consorzio has approved an additional 370 acres of plantings in 2023, suggesting that many more bottles of Alta Langa bubbles will hit the market in the coming years. Some producers are counting on Alta Langa’s connections with Barolo to open doors for them, hoping that, as more Barolo producers add sparkling wines to their portfolios, Alta Langa can leverage Barolo’s strong position in global markets.

For the near term, though, experts like Gabriele Gorelli MW see Alta Langa sparkling wines as appealing primarily to the Italian market, where some 90 percent of the bottles currently land. He finds Alta Langa’s linear style and assertive mousse to be more in line with Italian palates, where as Franciacorta’s lower elevations and warmer climate give approachable wines with generous fruit flavors; and Trentodoc’s largely chardonnay-based wines offer a richer, more autolytic character.

And yet, Gorelli muses, that Italian embrace of Alta Langa wines could become an advantage. “They can exude an Italian aura and create an authenticity that appeals to American sommeliers, the chance to show their guests something that real Italians drink.”

is the Italian wine editor at Wine & Spirits magazine.

This story appears in the print issue of Winter 2023.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.