Standing on a high, windswept ridge near the northwestern boundary of Chianti Classico’s Gaiole UGA, Alessandro Masnaghetti sweeps his hand from right to left, indicating Gaiole’s three distinct sectors. Toward the west, he points to a plateau near the village of Lecchi, where high elevations and white alberese soils predominate. To the south, around the village of Monti, he describes how those soils flatten into low, gentle slopes with thinner vegetation and warmer exposures. Swinging past the densely forested east, he turns to the northeast, where rugged hills covered with brown, sandy soils and thick forests climb toward the peaks of the Monti del Chianti chain.

Masnaghetti (aka Map Man) is fascinated by the diversity within Chianti Classico. In a sense, his cartography expands on the work of Burton Anderson 30 years ago, in his classic Wine Atlas of Italy. In Anderson’s book, the Chianti Classico map is one big green mass stretching from Florence to Siena. Expressing a prescient view, Anderson noted, “The problem is that Chianti Classico is not a single wine but a multitude.” He lamented slipshod winemaking and misguided viticultural practices while noting a growing number of fine estate wines, concluding, “Chianti Classico at its finest will be the privilege of future generations to enjoy.”

Fortunately, the future has arrived, and one of Italy’s oldest recognized wine zones is now one of its most dynamic. In a step toward recognizing Anderson’s multitude, in June 2021, the Chianti Classico Consorzio adopted eleven UGAs (Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive). When the new rules take effect this summer, Chianti Classico producers will be able to print their UGA on the front labels of wines made with fruit grown there, though initially only on bottles of Gran Selezione, the denomination’s top-tier wines that comprise just five percent of production.

Not long ago, the UGA concept stirred significant controversy among producers who opposed dividing this 184,000-acre denomination into smaller units. Today it is more common to hear arguments that the new rules do not go far enough. Many would like to extend UGA labeling privileges to Riserva and Annata wines, a refrain I heard a year ago when I visited Radda, where the UGA discussion has spurred producers to coalesce around a distinctive style for their wines (see In the Heights, W&S April 2022).

This year I went to Gaiole, to consider one of Chianti Classico’s most historically significant areas, and one of its most diverse. Following Masnaghetti’s maps of Gaiole’s three key sectors, and spending a day with the Map Man himself, I heard calls for recognition of ever smaller units to reflect this UGA’s territorial differences.

GAIOLE SOUTH

Barone Ricasoli

Masnaghetti begins his discussion of Gaiole here in the south, noting, “I had to take into account that the southern sector means Brolio, and that Brolio, in turn, means Ricasoli, and that Ricasoli is synonymous with Gaiole in Chianti and more generally with Chianti Classico, so it was clear that this sector had to take precedence over the others.”

Brolio castle is the ancestral home of the Ricasoli family, its oldest parts dating back before 1176 when it was captured by the Florentines. The red-brick façade overlooks rolling hills and white, rocky soils in the wedge of land that reaches to the southern border of the Chianti Classico zone. This is Monti, an area that Masnaghetti credits as having one of the strongest territorial identities in all of Chianti Classico.

Baron Bettino Ricasoli was a prime minister of Italy in the mid-nineteenth century who also created the modern blend for Chianti Classico wine, bringing sangiovese to the fore and supplementing with canaiolo and malvasia (a white grape). Up until World War I, the Baron’s descendants owned most of Monti, but by the 1950s their fortunes had diminished and they sold the Barone Ricasoli brand to Seagram, the Canadian drinks behemoth. The image of Barone Ricasoli’s wines declined under a series of corporate owners until 1993, when Francesco Ricasoli, a direct descendant of Bettino, pulled together a small group of investors and bought back the brand.

With nearly 600 vineyard acres, almost all in Gaiole, Barone Ricasoli is the largest privately owned estate in Chianti Classico, producing more than half a million bottles of Chianti Classico annata each year. Taking advantage of this scale, Ricasoli has initiated projects to gain a better understanding of his vineyards with the goal of producing more terroir-specific wines. “When I first took over, my export managers kept asking me to go out into the market, to be the face of the brand,” Ricasoli recalls. “I said no, I need to focus first on the vineyards, on the quality.” He commissioned a study in 2005, producing a 175-page report that detailed the microclimates and soil types within the estate.

Ricasoli used the study to identify three distinctly different sites, each of which now produces a single-vineyard Gran Selezione wine. All are 100 percent sangiovese and vinified in the same way, aging for 22 months in tonneaux, of which 30 percent are new. Colledilà, the cru closest to Brolio castle, sits at an elevation of 1,240 feet on alberese soils. In the 2019 vintage, it shows great depth and precision in its saline-infused dark fruit. Roncicone is about 200 feet lower than Colledilà, on a gentle slope of marine sands that give the wine a lighter color and leaner profile, with bright red-cherry flavors and raspy tannins. Due west of Roncicone is CeniPrimo, another 200 feet lower on an ancient river terrace, where higher clay content creates dense, compact tannins in the wine.

Ricasoli’s vast estate is the only one in Gaiole that can produce three Gran Selezione wines from such distinctly different soils and microclimates. Others, like his cousin Marco Ricasoli-Firidolfi at Rocca di Montegrossi, focus on a singular type of terroir.

Rocca di Montegrossi

Rocca di Montegrossi is Ricasoli-Firidolfi’s 277-acre estate that surrounds the parish church of San Marcellino in the heart of Monti. His name may be old, but the estate is young, founded in 1994 with an 18-acre vineyard that Ricasoli-Firidolfi inherited from his family. Over the years, he carved 30 more acres of vineyards out of the rocky soils, restored the dilapidated church, rebuilt the winery and created a charming agriturismo with beautifully manicured gardens.

“Monti is like the last terrace of the high hills of Chianti Classico,” says Ricasoli-Firidolfi, describing how Chianti Classico’s interior heights begin a gradual descent toward the lower, gentler slopes of Monti near the denomination’s southern border. “It’s very wide, so there is more circulation of air compared to farther inland. It’s a little warmer and the soils have a bit more clay, which gives great intensity and structure to the wines.” He makes two Chianti Classicos—an Annata and a Gran Selezione, the latter from the historic San Marcellino vineyard. The wines have a deep color and fine, elegant tannins that derive from the high limestone content in alberese. “We laugh when people say that sangiovese lacks color, because here it has a really deep, beautiful color—if you harvest at the right time and manage the extraction well.”

The broad, sun-drenched exposures in Monti lend a rich and earthy profile to the wines, and Ricasoli-Firidolfi enhances this powerful style by growing pugnitello to blend into his Gran Selezione San Marcellino. A local variety that he began planting 30 years ago, pugnitello yields small berries rich in anthocyanins that deepen the wine’s color and reinforce the structure. He grows some merlot and cabernet sauvignon, but does not believe in blending international varieties into his Chianti Classico wines, using those varieties instead to make two excellent IGT wines—Geremia, a merlot-cabernet blend, and Ridolfo, equal parts cabernet and pugnitello. As a member of the Ricasoli clan, it is not surprising that he identifies closely with Monti, and he hopes Monti will earn its own UGA status someday. “But it is also important that I’m in Gaiole, the most historical part of Chianti Classico,” he added.

San Giusto a Rentennano

A dozen miles to the south, at the end of a long, cypress-lined drive, I arrived at San Giusto a Rentennano and met Luca Martini di Cigala, a cousin of Marco Ricasoli. Still part of Monti, San Giusto feels completely different from Montegrossi. “Here the hills are open to the Colli Senese,” Martini says, pointing to the towers of Siena less than ten miles away and Monte Amiata just beyond. The estate is more rustic than Rocca di Montegrossi, with old farm implements scattered around the grounds and a dark, cave-like cellar housing dusty bottles dating back 40 years.

Martini moves comfortably through the vineyards, followed closely by his large, shaggy dog. Elevations are much lower here, averaging about 920 feet, and, while some of his 74 vineyard acres are on a mix of alberese and clay, others are rooted in about 15 feet of marine sands and pebbles over a deep layer of clay. He prefers alberello-trained vines in these sandy, low-vigor soils, explaining that the bush vines delay ripening through the dry season until rains can revitalize the grapes. Daytime temperatures are high enough that Martini has begun using nets to protect the grapes from sunburn, and he credits cooler night-time temperatures with preserving the bright acidity in his sangiovese.

San Giusto a Rentennano is probably most famous for Percarlo, a pure sangiovese first produced in 1983. Labeled as an IGT wine, it’s a reminder of the past, when producers rebelled against Chianti Classico’s rules requiring white grapes in the blend. Martini planted merlot in 1991, at a time when consultants were telling growers that sangiovese needed other grapes to soften its high acidity and angular tannins, but when Martini tried blending it into his Chianti Classico, he didn’t like the result. “Using French varieties in Chianti Classico historically was probably a mistake,” he muses, “although there are some wines with merlot that show real Chianti Classico character.” He now uses those vines to make La Ricolma, an IGT wine of pure merlot with distinctive Tuscan character and structure. As Martini notes, “It is more a merlot from a place than of a variety.”

Martini makes two Chianti Classicos, blending a small percentage of light-bodied canaiolo into the Annata and Riserva Baròncole. Both wines are lighter and redder in color those from Rocca di Montegrossi, their soft tannins and rose-petal scents typical of San Giusto’s sandy soils and more aligned with the bright red fruit tones of Barone Ricasoli’s Roncicone. Yet these are still robust wines with ample body that reflects the warmth of southern Monti.

Martini is involved in the Gaiole winegrowers’ association and says he has seen a shift over the years. “If you asked me 30 years ago to write the names of 30 wineries that do good work, I would have been in trouble. But today, I could name at least 50 or 60. They have moved the focus from marketing and branding to quality in the cellar and vineyard.” Noting the wide diversity within Gaiole, he thinks it should have been divided into at least three parts, but he admits that the UGA structure has had a positive effect. “Years ago people would talk about Chianti Classico, but not which Chianti Classico,” he says. “Now they are starting to talk about specific places in Chianti Classico, and this is very important.”

GAIOLE WEST

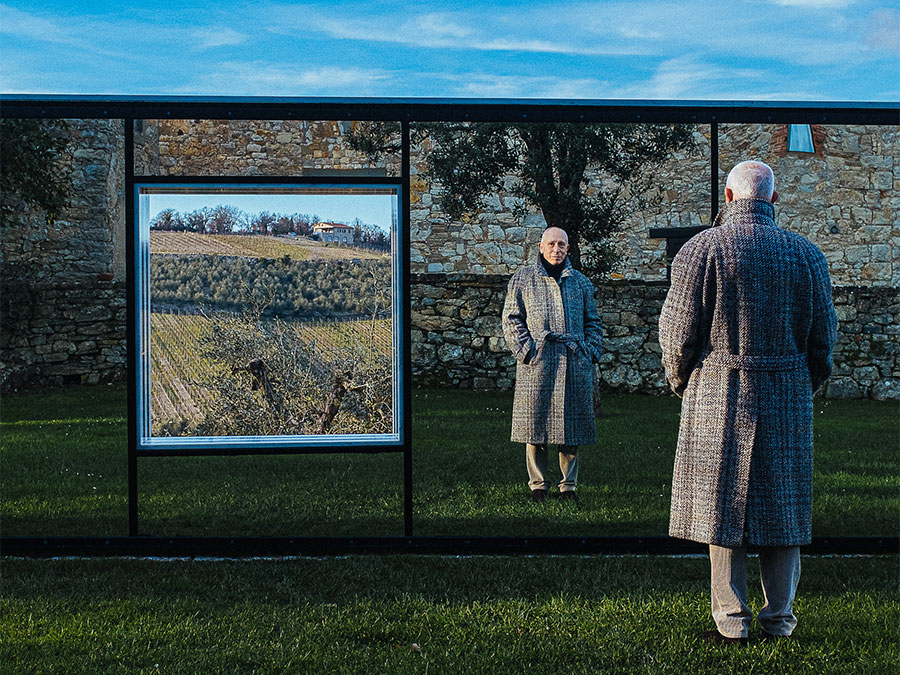

Castello di Ama

Moving from Monti’s warmth to the high, windy plateau in Gaiole’s western sector feels a bit like going from LA to San Francisco. Castello di Ama is one of the most historic properties in this sector, owned during the MiddleAges by the Firidolfi clan, which was long entwined with the Ricasoli family. Today, Lorenza Sebasti manages the estate, daughter of one of the four couples that purchased it in the 1970s. She works with winemaker Marco Pallanti.

Ama’s vineyards reach up to 1,730 feet a.s.l., among the highest in Chianti Classico. Although the whitish soils look fairly uniform, Pallanti has found enough variation in exposures and elevations to make five different Chianti Classico wines from Sebasti’s 185 acres of vines—Ama (an Annata), Montebuoni Riserva and three Gran Selezione wines—San Lorenzo, Bellavista and La Casuccia, the latter two from single vineyards.

Ama is more than just a winery; the complex of buildings and walkways are like a little village, all composed of the same hard, white-grey stones that are scattered through the vineyards. The estate is an interesting mix of traditionalism and modernity, the old stone buildings contrasting with a modern winery and a series of striking modern-art installations seeded throughout the property.

That mix also comes through in Pallanti’s wines, which combine tension and finesse. While there are differences among his Chianti Classico wines, there is a through line in the deep color and a refined tannic structure, a characteristic of wines from alberese soils. They also share the nervous acidity and piquant fruit flavors that come from these windy heights. His current releases emerged as some of the most complete wines in our latest round of blind tasting panels at W&S. Pallanti recalls that he planted merlot when he first arrived at Ama in 1982, and, unlike Ricasoli Firidolfi or Martini, who have made the decision to keep merlot and other international varieties out of their Chianti Classico wines, Pallanti remains committed to it, blending up to 20 percent of the variety into three of his Gran Selezione wines. Not surprisingly, he expresses some irritation over the fact that, when the new rules for Gran Selezione are finally implemented, international varieties will no longer be allowed. “I have worked on these blends for many years, and I have found what works. The merlot has adapted to this place,” he says. “The particularity of our wines comes from two main things: soil and elevation.

GAIOLE NORTH

Maurizio Alongi

I met Maurizio Alongi in the village of Gaiole, and we drove together past the outskirts of town, eventually turning onto a rough dirt road. Bumping through thick foliage, we reached an isolated slope of vines looking across a steep valley toward the medieval hamlet of Barbischio. This was unlike any other Gaiole vineyards I had yet seen—wild and rugged, silent and serene, as if from another time.

Maurizio Alongi is an outlier in this story, both in terms of history and terrain. “I was worried when I started this project,” he admits, “because Gaiole has so many heavy-weight producers with old families and important castles.” Maurizio has neither. He worked as a consulting oenologist for nearly three decades before he was able to buy some property of his own in 2015. His two plots in this secluded corner of Gaiole total just over three vineyard acres on macigno, a brown, sandy soil that is a complete departure from the hard, white alberese slopes of Gaiole’s south and west. Alongi’s vines were planted 50 years ago, at a time when it was typical to interplant other varieties with sangiovese—in this case, malvasia nera and canaiolo.

Down at Gaiole’s southern point, Luca Martini has to use nets to shield his grapes from sunburn. At Alongi’s vineyards, surrounded by woods and overshadowed by mountain peaks, he says that in the past it was hard to ripen the grapes here, where the microclimate is similar to that of Radda, just a few miles to the north. Now, with increasing temperatures, he finds his cooler exposition an advantage. Alongi makes just five thousand bottles a year under one label, Chianti Classico Riserva Vigna Barbischio, and he coferments the varieties in his vineyard before aging the wine in used tonneaux for one year, and 18 months in bottle. “My philosophy is to keep the wine a shorter time in wood and longer in the bottle,” he says, explaining that sangiovese grown on sandy soils like his have softer tannins than those grown on plots with more clay, and requires less micro-oxygenation in barrels to tame the tannins. We tasted Vigna Barbischio from five of his six vintages (he’s run out of the 2015, his first release), and, despite some vintage variation, the wines consistently showed high-toned red-cherry flavors, soft raspy tannins and bracing acidity, a style similar to the wines of Radda.

I asked Alongi why he labeled his wine as a Riserva, when it meets all of the requirements for a Gran Selezione. “When I started in 2015, those wines were all about richness and extract,” he explained. “I didn’t agree with this message, and the tasting committee wouldn’t have approved wines like mine that are lighter and more elegant.” He thinks that has changed, though, and he likes the idea of adding the name Gaiole to his label, which will become possible for Gran Selezione wines this year. “It is important for me to go slow, though, because this is a traditional area.”

The desire of some Gaiole producers to further divide the UGAs is understandable, and even admirable, as it stems from an intense focus on the particularities of their land. I am not convinced, however, that multiplying the number of UGAs will help consumers who are at the very earliest stage of encountering regional identity within Chianti Classico, and are just beginning to see wine lists organized by UGAs at restaurants like Babbo in New York and Acquerello in San Francisco.

The UGA structure, as it now stands, is a powerful concept—not just in a marketing sense, but because it has spurred producers to develop greater territorial consciousness, and that is driving quality higher. In Radda, this is playing out as a convergence toward a singular style. In Gaiole, a UGA that covers one-third more territory than Radda, the strength lies in its diversity, with multiple styles dictated by territorial differences and by the choices that producers make within the context of their land. But even as they push for further divisions, some producers still value the historical association with Gaiole—perhaps enough that they will allow wine lovers time to acclimate to the new UGA system, which is already giving shape and context to Anderson’s multitudes.

The Gaiole UGA map, courtesy of Alessandro Masnaghetti and Enogea, appears in our Spring 2023 issue or can be purchased here.

is the Italian wine editor at Wine & Spirits magazine.

This story appears in the print issue of Spring 2023.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.