Once a month my family would go out to eat at Hong Kong Restaurant on Spenard Road in Anchorage. The waitresses watched us all grow up, she knew what each of us liked eating, and my mom would get a glass of plum wine with dinner. That was my extent of engagement with wine.

But also, Alaska is extremely remote, and the life I lived there was very much outside, with lots of interesting plants, and the changing seasons changes the smells of those plants, and I paid a lot of attention to that. My uncle, I found out later, actually went around doing this too. His nickname was “Nose.” Urban areas aren’t like that. But wine has that.

In terms of a signature wine experience: Right at the beginning of my 20s, all of my friends were much older than me. They bought me, I don’t even know, but a bottle of high-end Chianti for a birthday present. That was the first time I tasted wine and thought: This is really good!

I got into Chianti because of that. And then a couple of years later, I watched my sister’s daughter for the summer so my sister could commercial fish, and my other sister watched her sometimes, too. At the end of the summer my sister took both of us out to dinner and decided she wanted a nice bottle of wine, and ordered a premier cru Burgundy. And that was the first time where it was like: everything in that glass wanted me with it. It was wild. It wasn’t just that I wanted the wine; it was like the wine wanted me too; that level of intense intimacy. I had never experienced that consciously with a drink or a food. I couldn’t believe how it smelled, and it was so delicious and intriguing. Again, Alaska has really earthy smells. A bit of rotten leaf, a bit of sour berries, things like that. And Burgundy has more that direction of aroma and flavor.

The Chianti made me realize I could really like wine; the Burgundy made me realize there was something there that was irreplaceable.

And after that, any wine I had, I needed to know what the grape was, where it was from, was that typical of the place. I got that curious ferocity at that point.

How did you go from teaching philosophy at Northern Arizona University to blogging about wine as Lily-Elaine Hawk Wakawaka?

I realized a year before I left academia that I needed to get out of academia. I gave myself a year, to do it gracefully.

The thing about being a professor is that, in a way, the smallest portion of what you to do is actually teaching classes: it’s always ordering books and planning classes for the following year, keeping your research going, presenting at panels and conferences. And during the final year I stopped doing all of that. I had this massive cavern of headspace I had carved out purposefully for my profession, and I needed something to go in there. I realized I needed something different to do that was totally removed from this highly verbal, intellectual life I was living, so I started drawing a lot, and I started spending a lot of time with wine: it was all about smells and textures, all about sense pleasure.

One day I thought: Oh my god, I’m going to draw wine comics! [Her first blog posts were illustrated wine reviews.] The contrast made me laugh—wine is so elevated, and comics are so pulpy. And because I had this other profession and wasn’t out in the open yet about leaving it, I needed a new name. The first three parts—Lily, Elaine and Hawk—anyone who knows me well knows at least two of those names. And then “Wakawaka” just makes it all work. So it wasn’t my name, but friends and family and people who knew me well could tell it was me.

How would you compare writing about philosophy to writing about wine?

In some ways it parallels the challenge with philosophy, which is one of trusting yourself. In that way, I’m grateful that I was in philosophy before. A friend of mine in grad school said, “There’s only one thing you need to know to get through it: grad school is a machine for generating paranoia and self-doubt, and if you’re feeling those things, you’re doing it right.” Doing doctoral work in philosophy is this brutal suffering of those feelings.

This last week, one of things Jancis [Robinson, one of the speakers at the Symposium] told us was that wine keeps us humble. And the idea was that, if you feel that, you’re doing it right. Your mood changes, the wine changes with time, the food changes the wine, the circumstances in which you taste the wine change and your own relationship to the wine is always changing. There’s an incredibly humility in that, that hopefully we can learn more grace through.

The truth is that I push myself pretty hard, but what that means is that I’m pushing myself further into doubt.

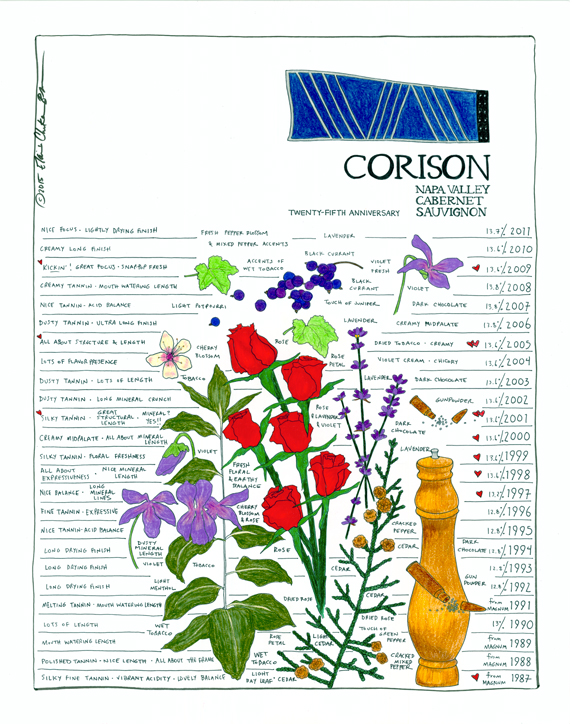

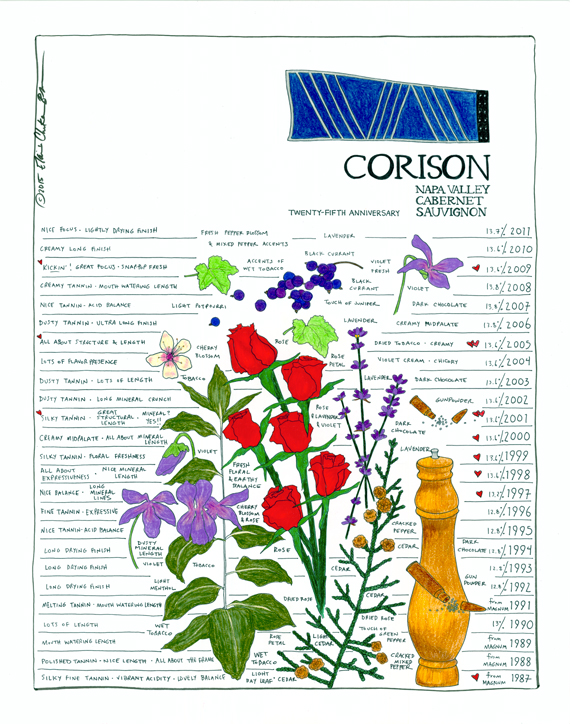

You’ve been making some more ambitious wine drawings of late.

I hit this point where I had done so many of these tasting note drawings, they were getting rote for me, so now I do each one on formal art paper with art supplies, so each wine is an art piece. Before, I was drawing them on copy paper. I needed to re-engage with what I was doing, so I needed to up the ante on myself. Recently, I’ve been letting myself play with the form.

I did a vintage vertical representation of Cathy Corison’s Napa Valley cabernet because I got to taste that with her a few months ago. It was a rare treasure: to get to taste a full portfolio of someone’s wine, and a wine that’s had quite an impact on a lot of people.

Wine is a really sensory thing. When we analyze wine and put it into words, it removes us from the senses and puts it into the abstract imagination. Which is a useful process, but that’s not where wine lives. Doing a visual representation of a wine keeps wine in the realm where it lives—which is the senses, you know?

This is a W&S web exclusive feature.

illustration by Elaine Chukan Brown

Longtime senior editor at Wine & Spirits magazine, Luke now works for the Stanford Technology Ventures Program.

This is a W&S web exclusive. Get access to all of our feature stories by signing up today.