Carménère found a home in Chile safe from phylloxera, the plague that had destroyed its roots in Bordeaux. The vine is particular and doesn’t cotton to American rootstock, though its own roots thrive in American soils, particularly in the Andean foothills and the coastal valleys south of Santiago.

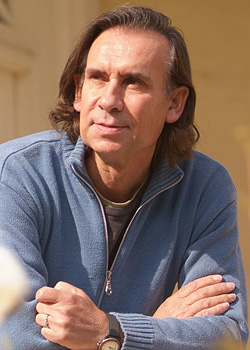

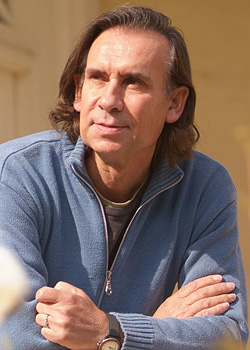

For more than a century, Chileans thought of their vines simply as from Bordeaux and no ampelographer was there to tell them their mix was substantially different from the contemporary, post-phylloxera plantings of cabernet sauvignon, merlot and cabernet franc. Though the vine they called merlot often ripened after cabernet, no one questioned its behavior until Alvaro Espinoza, son of a noted enology professor at the Catholic University in Santiago, started farming the vines at Ricardo Claro’s estate in Buin. Claro had hired the young enologist to establish a new winery, Carmen, and Espinoza asked a visiting ampelographer to check out some vines that were not behaving like the others. Jean-Michel Bourisquot determined they were carménère, aka grande vidure, and Espinoza went on to bottle the first wine labeled with the variety in the New World.

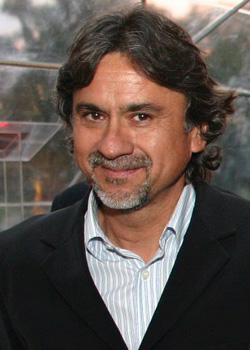

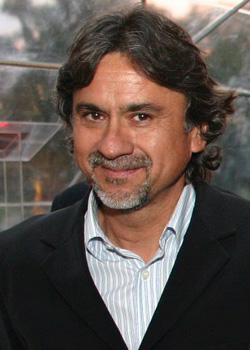

On a recent visit to Chile, I caught up with Ignacio Recabarren, the legendary winemaker behind Carmín de Peumo, to talk carménère. He met me at Concha y Toro’s Pirque estate with eight vintages of his Terrunyo Carménère and four vintages of Carmín. “With Terrunyo, I’m trying to make the wine as simple as possible, a wine that’s directly from the soil. Carmín is a luxury wine with more layers,” he explained. The Carmín wines are richer in alcohol, bolder in flavor, dark, truffley and formidable. The Terrunyo Carménère, especially in cool vintages, is more elegant, with a textural grace that defines the variety for me.

“Before phylloxera,” Recabarren told me, “carménère was fifty percent of Bordeaux. I try to imagine our wines as second growth Bordeaux and that makes me happy.”

Recabarren made the first Terrunyo Carménère in 1999, a wine from block 27 at Concha y Toro’s Peumo Vineyard, a terrace on the north bank of the Cachapoal River in Chile’s Rapel Valley. “At the beginning, we worked close to 14.8, 14.9 degrees of alcohol,” he says about that first bottling. “Now, since 2008, we are targeting 14.5, 14.4.” At that level, he describes the variety’s expression as linked to a sotobosque scent, violets, blueberries and a little cherry. He describes Peumo as a place that grows delicate carménère, compared to the more wild and powerful wines of Apalta. He’s also intrigued by the Miraflores site, in the Andean foothills, where Casa Silva grows its Microterroir Carménère.

The warm 2003 vintage produced Recabarren’s first bottling of Carmín—15.2˚ alcohol and 24 months in barrel. It’s supple, intense and truffley with the black fruit of Block 32. The vintage also built sweetness into the Block 27 Terrunyo, along with tobacco scents and a long stretch of tannins.

But it’s the cooler vintages that were my preference in this Peumo tasting, with the 2004 Terrunyo about as silky as carménère can get, a dark wine with the quiet persistence of moonlight. Decanting brings up the mineral detail in the tannins. The 2010 is plump, deep in its red fruit, the tannins feeling gras and elegant. That generosity goes a step further in the 2010 Carmín, a bold and juicy wine with scents of wild mushrooms.

There were several standouts among the younger, cool-vintage wines. One was the 2013 Lote 1, a selection of 4,000 bottles from the heart of the block 27 site. It spent only six months in barrel and was bottled a month later than the 2013 Terrunyo. The wine already has a remarkable floral character and blueberry freshness.

And the 2011s, both Carmín and Terrunyo. Carmín is a formidable red that maintains its elegance, achieving the knife-edge balance of power Recabarren has been striving to grow into his carménère. True to its Bordeaux heritage, this is the kind of wine that requires aging to show itself. You could enjoy its Beyoncé flash now, but you would be better off waiting ten years for more intricate pleasures.

The 2011 Terrunyo Block 27 combines the richness of fruit and texture in a way that only carménère can—think satin-textured fruit and silken tannins. The umami notes of earth and tobacco are precursors of the complexity that will develop. The coolness of the vintage and the surety it displays as a young wine trumps the 1999 at the same age. In a dozen years, this should prove astonishing.

Here are my notes on the 1999 from February 2002: Chilean vineyards were planted by the Bordelais, and Chilean winemakers still look to Bordeaux as a model for their reds. So it’s tempting to compare a wine of this stature to Bordeaux, even if the French don’t grow carménère much anymore. It has the deep purple color, the beautiful robe you might associate with top-flight contemporary Bordeaux, but beyond being in their class, it has little else to do with such wines. Instead, it speaks of the Chilean mountain air settling on the vineyard at night, bringing the tart cherry flavors into a darker succulence, of the sea breezes bringing their own sort of austerity to the setting of the fruit. This is grand in its exposition of flavor, radiant in the projection of that flavor out of the glass. And yet, for now, it’s all balled up, black and gripping, a carménère to push to the limits of its cellar life, just to see what that might be.

This is a W&S web exclusive feature.

Joshua Greene is the editor and publisher of Wine & Spirits magazine.

This is a W&S web exclusive. Get access to all of our feature stories by signing up today.