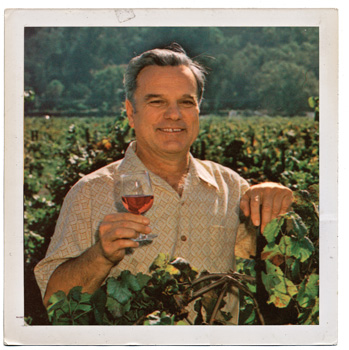

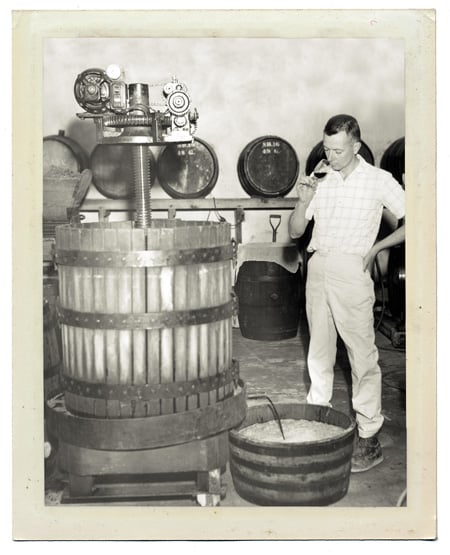

Peter’s father, Cesare, purchased the winery in 1943, but Peter’s brother, Robert, had just exited the family business after a now-legendary fight, and was in the process of building his own winery a few miles south—while still borrowing equipment from (and using the presses at) Charles Krug.

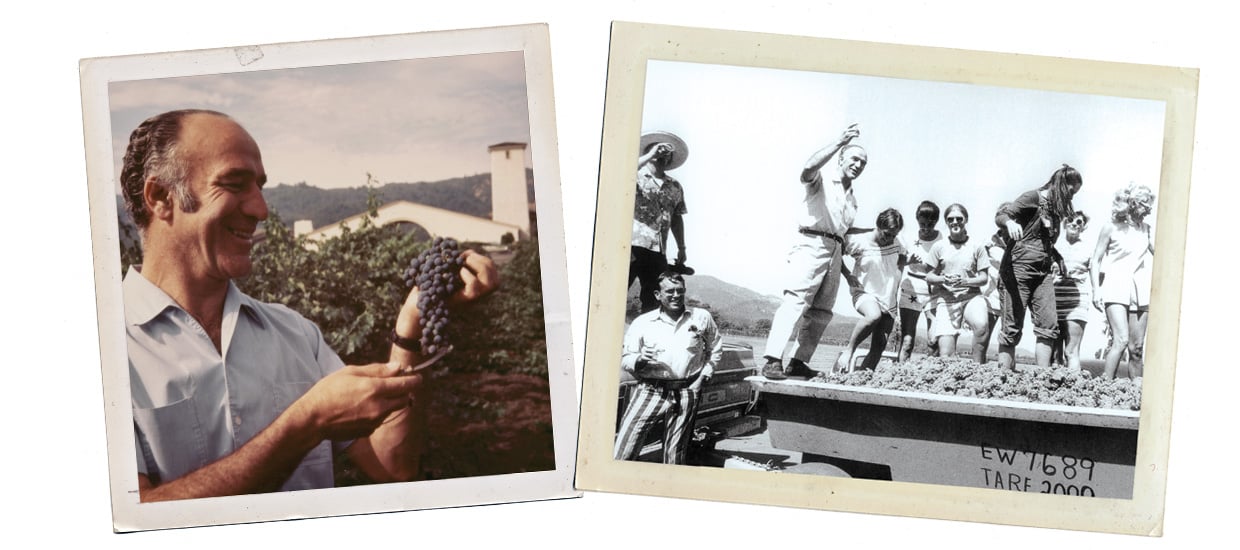

In those days there were only a few dozen wineries in Napa. Robert Mondavi’s ambitious and rapid construction project must have been the talk of the valley. The first grapes were brought to the Robert Mondavi crushpad—the winery was still not completed—in mid-September: pinot noir from the Mondavi family’s surrounding To Kalon Vineyard.

A prime location on Napa’s gravelly western bench, To Kalon was originally developed by H. W. Crabb in the 1870s, and became one of the first significant vineyards in Napa Valley. The To Kalon

Vineyard itself would remain in legal limbo until 1977, when a lawsuit between the two brothers was settled, and most of the vineyard went to Robert. Peter, meanwhile, was still reliant on To Kalon in 1966—his Vintage Selection Cabernet that year was sourced largely from that vineyard, with small contributions from the Krug Ranch in St. Helena and Nathan Fay’s pioneering vineyard on the east side of the valley in Stags Leap. One might imagine the picking crews that year dishing about the rift between two of the valley’s most prominent proprietors amid the old head-trained vines of To Kalon.

While the harvest may have been challenging for both Mondavi brothers, the vintage itself was good, if cool—André Tchelistche, at Beaulieu Vineyard just to the north in Rutherford, apparently preferred it to the lauded 1968. Tasted today, the 1966 Charles Krug Vintage Selection still feels quietly confident. The scent is sweet and tawny, fully resolved but very much alive, the acidity carrying a ghost of red fruit and the savory, elusive bouquet of old cabernet in a seamless line of fl avor—an antique, rosy whisper of a wine. It’s an increasingly rare glimpse of early genius at one of Napa Valley’s most coveted terroirs: the gravelly bench (really a series of interlocking alluvial fans) that extends along the western side of the valley from Yountville in the south to St. Helena in the north. No other stretch of land in California has produced so many legendary, classic examples of cabernet.

But what was so compelling about those early Napa cabernets? And how do they relate to the wines being made today on those same benchland sites? Is there any continuity between those earlier classics and today’s potential classics?

The Classical Era(s)

1966 Charles Krug Vintage Selection Cabernet

1969 Beaulieu Vineyard Georges de

Latour Cabernet

1970 Freemark Abbey Bosché Cabernet

1977 Robert Mondavi Reserve Cabernet

1978 Heitz Martha’s Vineyard Cabernet

“How nice the wines are generally,” Gerald Asher said after we spent some time quietly exploring these venerable examples of Napa cabernet. “They are very typical of Napa Valley, with their balance, and the warmth of the wines. They are much as I would have expected.”

Like the 1966 Krug described above, Tchelistche’s 1969 BV Georges de Latour felt savory and similarly elegant, tart yet polished. The 1970 Freemark Abbey Bosché—the inaugural vintage of one of Napa’s first single-vineyard cabernets—was a bit tougher but very reserved, its shyness perhaps due to slight cork taint.

“There’s nothing unnecessary or excessive,” Yoon Ha commented in regard to the three oldest wines. “No bells and whistles.” He was particularly taken by the 1966 Krug, referencing the Japanese term

shibui, which he phrased as the art of “simplicity, beauty and purity.”

“What was the mindset of the people making these?” he wondered.

Luckily, we had Asher on hand, who had spoken to many of those who had made wines at the time. After Prohibition, he reminded us, few people even remembered how to make fault-free wine, and that became the first priority as the industry reemerged after Prohibition and World War II.

“They felt that if they made wine free of faults, people would appreciate it for what it was,” he commented. “Whatever they did or didn’t do, it comes through as a wine where nothing seems warped—it’s extraordinary when you think about it. They just made the wine.”

Asher pointed out that, in 1966, Peter Mondavi, Sr., at Charles Krug, would still have been making the wine in redwood vats. “I doubt there was new oak on this wine,” he added. (A follow up query to Peter Mondavi, Jr., was inconclusive. The wine was indeed fermented in redwood, pumped over rather than punched down—perhaps that explains the delicacy of the tannins—then moved to mostly French oak, though the age of the oak isn’t recorded. The firm may have already been moving toward new oak, which would soon be the de rigueur method for making cabernet at Charles Krug and every other winery in the valley.)

It soon became clear that this wasn’t a lineup of similar, decidedly old-school Napa wines. It was apparent that we were witnessing a slow revolution taking place, or at least a distinct linear progression.

“Wasn’t it interesting to compare the ’66 Krug with the ’77 Mondavi?” Asher asked. The two wines were both based on cabernet from the To Kalon Vineyard, but clearly represented two different eras, a mere decade apart. Asher pointed out the increased role of technology in the cellar through the 1970s, from stainless steel equipment to much more sophisticated analytical tools. And with that came a change in attitude.

“Robert Mondavi didn’t let the wine come out,” Asher argued. “He made it what he wanted it to be. He used to talk about ‘peeling the onion.’ He wanted to make very structured wines.”

In the case of the 1977 Reserve, the wine was, in fact, made in roto-fermenters, which churn the grapes during fermentation, resulting in a sometimes heroic payload of tannins.

But the differences were about more than just winemaking. Moving from the 1966 to the 1978, Haley Moore noticed a trend of increasing ripeness in the wines. Whereas she found the Charles Krug and BV to be leathery, mineral and subdued, she noticed both green notes and a riper tannin texture in the Freemark, and began to feel an alcohol warmth in the 1977 Mondavi and the 1978 Heitz. She was right: the stated alcohol levels slowly rose through the tasting, from 12 percent in the 1966 Charles Krug to 13.5 percent in the 1978 Heitz.

“Joe Heitz’s wines were always quite massive,” Asher said, “But he made wine with everything in proportion. They are like highly polished Victorian furniture. Lots of knobs and things, but all polished—everything fitted in.”

“It speaks to me,” said Johnny Slamon. “Exotic aromatics, minty, explosive—the brightness, red fruit, herbal, tobacco. That green-pepper spice we try to get rid of today. It’s not a Napa cabernet of punchiness—more floral. Elegant.”

The 1977 Mondavi, meanwhile, while certainly ambitious, was a lovely wine in its own right—showing the coffee-scented influence of French oak but focused on clean, vigorous dark fruit flavor, still remarkably firm and fresh. Of all the wines in the tasting, it seemed to gain the most from air, holding its freshness over the course of an entire week while the other wines faded, one by one.

If the 1966 Charles Krug is a classic example of a style of Napa cabernet that was already on the wane, perhaps we could say that the 1977 is a classic rendition of a new, emergent style: still true to the vintage (the concentration of a drought year), the vineyard (the tension between lusciousness and firm structure inherent in To Kalon) and the precision of UC-Davis-trained winemaker Zelma Long, who was then making the wines, with Robert’s son Tim Mondavi serving as assistant winemaker.

For his part, Asher argued that the 1969 BV Georges de Latour might be the ultimate classic. With André Tchelistche at the helm from the 1930s through 1973, the wine maintained a remarkable consistency of style: 100 percent cabernet from BV’s vineyards on the Rutherford bench, aged in the firm’s signature American oak barrels.

The sweet impression of American oak that made Georges de Latour from that era so distinctive was barely noticeable by this point—most of our panelists missed it until Asher pointed it out. The tannins felt less ripe than is the current fashion, but also less heavily extracted. The wine only got better over the next day, long after the tasters had dispersed, opening into bright red raspberry and raspberry leaf aromas, its mouthwatering fruit zesty against the warm earthiness of its structure.

“It was a classic in the best sense of the word,” Asher said. “There were elements of style that were consistent. If you tasted the 1968 and the 1974, you would know that the difference between them was a difference of vintage. It was a yardstick kind of wine.”

And Now?

To consider what might constitute the future classics in the current era, we blind tasted a dozen 2012 Napa Valley cabernets from the same stretch of benchland terroir that gave rise to the older wines. Does the western bench still produce classic cabernets?

At Alexander’s Steakhouse, Slamon said, he sells plenty of cabernet, but few guests are interested in older wines. Most of what he sells is four to seven years old.

“Diners who spend $300 on a 2007 Napa cabernet would reject this wine,” he said of the 1978 Heitz. “They would find it unsound.”

In the 1970s, many Napa Valley winemakers felt they were competing against the French, and hoped to prove their worth with wines that had the firm, ageworthy structures of good Bordeaux.

Now, with the market focused on younger wines, designed to show luxurious fruit and soft tannins in their youth, that Bordeaux paradigm has long been on the wane.

Indeed, the 2012s we tasted leaned toward ripe, sometimes roasted or candied fruit flavors, often with a chocolaty density, contributed by new oak, and chewy, heavily extracted tannins. (“Too much information,” Gerald Asher said about one of the less successful wines in the group.)

While many were delicious in their way, three of the wines seemed destined to show life and typicity in 20 or 30 years’ time, with structures that felt connected to place, to the cool evenings, warm afternoons and gravelly soils of the western Napa Valley bench.

2012 Dominus Napa Valley

2012 Spottswoode St. Helena Napa Valley Cabernet

The 2012 Spottswoode had a rich, tobacco-laden fragrance that became more captivating with air, the tannins omnipresent yet fine and supple, the warmth of the fruit channeling sunlight rather than sugar. “It’s a big wine—firmly structured and weighty, but balanced,” said Haley Moore. “Ripe, plenty of skin tannins, but probably the most ageworthy.”

2012 Robert Mondavi Winery To Kalon Reserve Oakville Cabernet

Ripe and sappy at first, the wine coalesced along a stony line of tannins that lasted. It had real stature, the structure at the end of the wine focusing it on complex spice, rather than just fruit.

“You can taste the future in it,” commented W&S Napa critic Joshua Greene.

This story was featured in W&S Fall 2015.

illustrations by Michael Hirshon

Longtime senior editor at Wine & Spirits magazine, Luke now works for the Stanford Technology Ventures Program.

This story appears in the print issue of fal 2015.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.