As someone who’s made a business out of describing wine with words, I was interested to read the perspective of an English professor who teaches literary criticism and also happens to love wine. Michael Sinowitz, in his new book, Finding Meaning in Wine, draws parallels between literary critics and wine critics, considering whether their efforts to interpret wine through words is anything more than a fool’s errand. Having been interviewed by Michael, then having invited him to taste with one of our panels, I interviewed him to clarify and expand on some of the discussions he raises in the book. Here are a few excerpts from those interviews. —Joshua Greene

WORDS

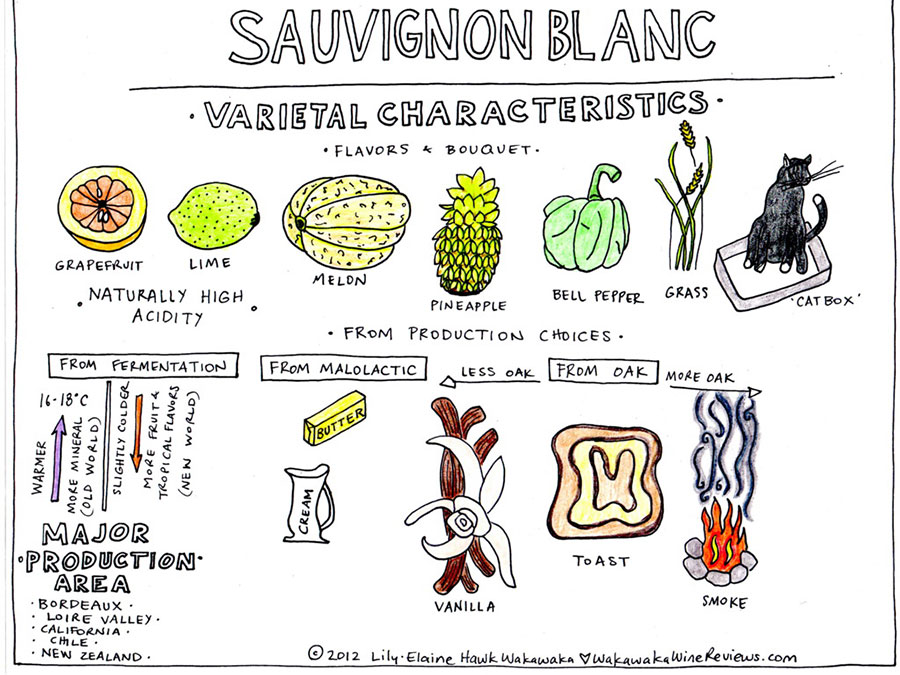

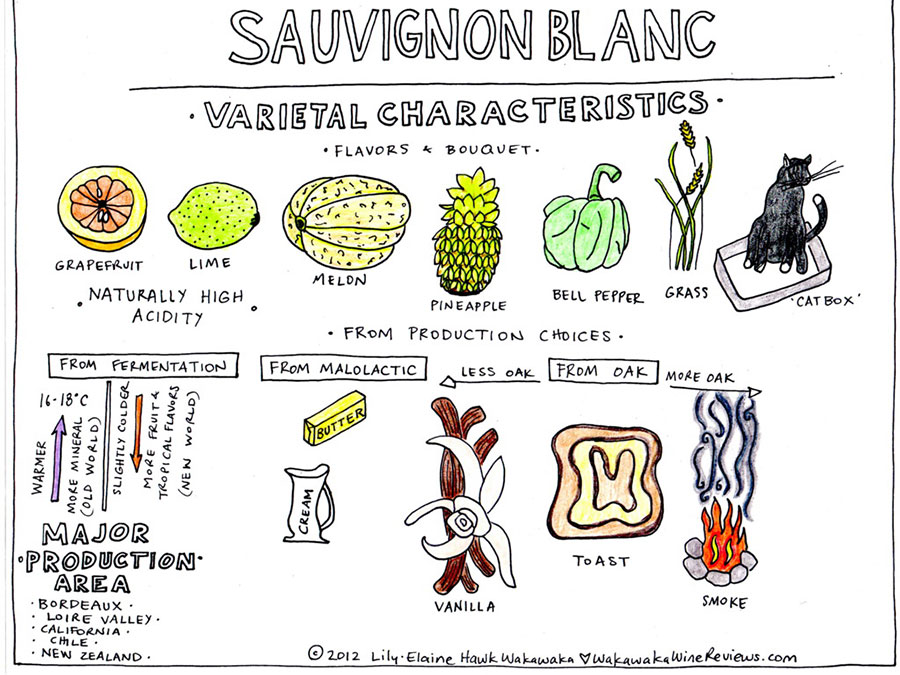

JG: You cite examples of tasting notes in your book, including a number that read like a string of fruits, interspersed with words that amp them up. I always wonder how much that kind of description actually communicates.

Michael Sinowitz: It always struck me as a way to display your skill: the more you can sense and translate, [it can become] almost intimidating. In the way I was intimidated in my experience in the Wine & Spirits panel.

JG: Most everyone you interview about interpreting wine with words—or numbers—has a different approach. All of them are problematic in some way. Do you think there is an effective way to approach wine with words? We can all sit around and just drink wine, but if we’re going to discuss it, we need words. Or maybe there’s no reason to discuss it.

MS: Well, then both of us have been wasting a lot of time. When you start talking about this, it puts me in mind of the old joke Woody Allen tells at the end of Annie Hall, about relationships, “Well, we need the eggs…”

I would say, obviously, if you are going to talk about [wine], you do need words. Part of what I interpret is that a part of what makes someone a talented taster is their translation skill. But it is interesting that a lot of the disagreement in the wine community about this is tied to a kind of anxiety about words. In the sense, can words accurately convey meaning? Can they convey a limited meaning?

I think that attempting to narrow the way words work is faulty. I don’t see language that way. I am at least sympathetic to this idea from the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, that language tends to spill further meanings, that when you use metaphors, it tends to produce more metaphors, what is called in literary studies a “chain of signifiers.” That doesn’t bother me. It’s par for the course that we will be that way when we use language.

But it’s tricky, in the sense that Derrida is famously a writer people find incoherent and unable to process when they read his work. So, for someone like yourself, or anyone who is writing about wine, it’s sort of important, that it not become that way. How else are you going to convey your experience if you can’t produce it in a way that other people can understand it?

STORYTELLING

JG: When I read the first chapter of your book, “Against Tasting,” it led me to consider my own experience with wine, whether at dinner, or tasting with winemakers in their cellars, or tasting blind. I have strong memories of wines at all of those settings, but the clearest memories of wines that I tasted blind.

Maybe that’s because one of the reasons blind tasting appeals to me is that it allows me to use a stream of consciousness approach to describing a wine. If I knew what the wine was, my brain would already have a flashpoint of information that I would then be stuck circling around. But not knowing what it is, it allows me to use one metaphor and then another and another, and then when I look at all of those things and find out what the wine is, and find out what they did to the wine, and find out how it was grown or where it was grown, one of those metaphors usually has some pertinence or value. And it’s not necessarily the same old bullshit, a spewing of wine descriptors. It has more to do with different memories in my brain that I can try to share with a reader. In the end, that process helps me develop a memory that sticks.

MS: So, you have this experience, and you start building a kind of narrative of connection between your experience and who produced it, what it is, how they produced it, and that becomes a way of your sensory reaction and experience becoming coherent.

I once got into this long argument with an art historian who used to work at my college [DePauw], about whether or not narrative was a part of interpretation. We got into this argument about how one makes sense of a still life. Narrative is part of the process we use to make sense of an image like that. We attempt to contextualize it.

JG: You quote Eric Asimov’s contention that “history and intention count for much” when considering a wine in the glass in front of us. It’s why Eric takes a stand against blind tasting, and advocates for telling stories instead. Of the many camps of wine criticism you describe, there are advocates for just recording the experience; or for sharing the experience of tasting the wine in the context of how the wine came to be; or for focusing on telling the story of how a wine came to be worthy of attention, and how it might be similar or different from others that are worthy of attention.

MS: But [writers like Eric] are not completely separated from the experiences. There’s some element of that immediate reaction in his writing.

JG: No question, but it seems to be a question of how much we focus on those immediate reactions. In any case, doesn’t the culture place more value on storytelling than on wine tasting?

MS: To a large extent, yes, but I’m immediately thinking about the shrinking [number of] English majors across the country. I see English majors as part of the preservation of storytelling, to some extent. When I first got to DePauw, in our senior class, we would have two literature senior seminars and up to five writing senior seminars. Now, the current senior class has two literature students in it. And, at the most, we are having two writing-major seminars. Our numbers are dipping drastically that way. That’s a national trend, it’s not unique to us.

JG: So, you see that as people not going into storytelling.

MS: No, [they’re not.] DePauw just started a school of business and leadership. It seems to me that’s where the message lies as to where the priorities and resources are going. On the other hand, we almost went through a national crisis during the writers’ strike in Hollywood, because we need content. It’s certainly there in some forms, it’s just the older tradition is sort of fading.

Rhetoric

JG: I hadn’t noticed how many manifestos have been written in the wine community, but your book points out a number of them, and then you go on to consider their impact. More than the lengthier manifestos, it seems to be the words different groups use to name themselves that amplifies that impact. The writer Alice Feiring frames her advocacy for “natural wine” as a battle. And you’ve assembled a history of “In Pursuit of Balance,” the group founded by Jasmine Hirsch and Rajat Parr, specifically focusing on the battle among winemakers inside and outside of the group about the word “balance.”

MS: Part of the way the battle was formed is that they found a way to frame it that got people’s attention. There’s no doubt that homing in on just the word “balance” became a pivotal part of it. I could see the physical discomfort of some winemakers when I brought it up. They felt it was an insult to them, in some ways.

JG: As in, the people pursuing balance at a different level of alcohol. Which is what they end up saying: “Why can’t I pursue balance at 15 percent or 16 percent? The wine is still balanced.”

MS: To me, in the case of In Pursuit of Balance, there were not just words but rhetorical strategies in what they did; and the champions of natural wine, like Alice Feiring, are extremely tied up in trying to be persuasive. That is part of the way in which the language itself is being used. I was struck by how the words “balance” and “natural” should be pretty banal in the world of wine. They likely would have been except for the kind of rhetorical thrust that implied, and sometimes went beyond implication, that you weren’t making wines that were balanced, or that you weren’t making wines that were natural.

One of the points I was trying to make in the book, those folks who have been attached to those movements, and there is overlap, were attempting to convince people—and this is the commercial aspect—to either judge their wines differently or reconsider how they were judging wine.

So it’s sort of the inverse of trying to translate the experience of wine into words. Here it’s using words to try to manipulate your experience of the wine. To me, that’s one of the fascinating things about what both of those movements have done. I think it is a neat trick to have been able to stir the pot as much as both of those groups have done.

BELIEF SYSTEMS

JG: Natural wine has actually become a commercial phenomenon. But, to be part of it, winemakers often present themselves as part of the natural wine tribe.

MS: Particularly with natural wine, it’s fascinating the way in which this sort of test of purity is in operation. In one of Feiring’s books, she tells the story of an American making wine in the Rhône, who is in tears because she’s not sure if she is meeting the purity test. And Tegan [Passalacqua] tells a story about being told that his wines are too clean. It’s also fascinating that it’s clearly a very slippery slope. Obviously, there are people trying to get purer and purer in their natural bona fides, but there are people at all points in the spectrum out there.

Of course, that also makes it feel inherently political. The natural wine movement and In Pursuit of Balance were effective because their rhetoric created an opposition. Or made a lot of people feel challenged. The most defensive person about balance seemed to be [Robert] Parker. He essentially pulled a sort of Trumpian gesture of coming up with a nickname to attack. And I had this experience of talking to Raj, who is like, ‘I can’t believe this happened.’ Of course, you have to believe it happened. This is what you wanted, right?

JG: In reading your book and thinking about your book, what struck me was all of this lip service that’s given to, “Well, everyone’s entitled to their opinion.” Which everyone agrees on. But nobody seems to agree that everyone is entitled to their belief system. And we all have different belief systems. I’d always thought about the differences in wine culture and wine tribes as being based on opinion, rather than on differences in belief systems. You talk about metaphysics in the context of literature and literary criticism, and, in parallel, you discuss wine criticism and people’s approach to wine. It seems to me that a lot of these battles people are having is an unwillingness to accept that other people have a different belief system, a different world view.

They are differences of belief systems rather than differences of opinion.

MS: That’s absolutely the case. What I was tracking was how these opinions fall into different belief systems. One of the things I talked about, in terms of the way different beliefs about interpretation tend to fall, is the question of what counts as evidence. That’s one of the places where things divide, when what counts as evidence does not overlap and can’t be reconciled…or there’s not a desire for reconciliation of those possible viewpoints.

EVIDENCE

JS: When you talk about evidence, the discussion turns to science and observation. In fact, science is not considered as evidence by some cultural groups.

MS: That is what’s built into the Feeling and Reason divide I try to talk about throughout the book—that evidence is open to interpretation or difference in the first place. In literary circles, I would say that the most challenging of all areas of evidence is with Freudian approaches to literature. At DePauw, I teach a course of literary theory where we go through these schools of interpretation and there’s one week where I do psychoanalysis. I always try to frame and say, ‘You’re going to be very upset with me for this entire week,.’ And they are; and it’s partially because they will not accept what psychoanalytical critics say counts as evidence—the unconscious desires of the author. First of all, how are we going to be sure? The students won’t accept it. It’s the most radical of examples in this regard.

There’s that moment in my conversation with Ted Lemon [of Littorai], where I propose, I now think rather naïvely, that he put biodynamics under the scientific lens. And he’s like, ‘Oh no, I’m not going to do that.’ That would be a movement toward suggesting there is one type of evidence, which is not what Ted wants to do with his biodynamic farming. There’s a really interesting part where he is explaining to me his evidence for how he knows biodynamics works. And it’s his observation of his vineyards, not something that’s being put under the process of the scientific method. What I was suggesting was that if you want to convince people who don’t buy into biodynamics, have something along these lines, but that’s the line he did not want to cross.

I got all kinds of responses [to questions about biodynamic practices]—some saying that the biodynamic sprays are too powerful. [Or] that there’s no way they could possibly be powerful. That it’s not biodynamics; it’s the fact that it forces people to pay so much attention to their vineyard, so that [the vines] will actually stay alive. Because there’s no test of evidence that people will agree on, there’s no way to sort through those various arguments about what is actually happening. I remember being so surprised at both Beinstock [Gideon, of Clos Saron] and Beckmeyer [Hank, of La Clarine Farm]—I actually interviewed them back to back—telling me the sprays were too powerful. By that point I was thinking that was not something I would actually hear. I guess if I went further and further out into California, I’d hear all kinds of different things.

CREATIVITY

JG: For your third chapter, “Death of the Winemaker,” you ask a number of winemakers whether they consider themselves artists or craftspeople. As I read about the various ways they would bristle in response, I wondered about the development of their taste memory and the use of their taste memory in making decisions, based on their observations. To me, that’s a creative, or an artistic pursuit. Musicians will often hear music in their heads and will write it down. A sculptor will describe how he sees a shape in a stone and carve it out. And the original shape of the stone will determine the work that sculptor is doing. They see something or hear something that they then act on and use in a creative way. I think about taste memory and scent memory as being that skill that an artist would have if an artist were a winemaker. Formulating scent memories from what you are feeling in the place where you grow grapes, the soil there, the things that grow around your vineyard, what you taste when you taste the grapes before harvest, what you taste in the fermenting tank. A winemaker is guiding that in the same way that a sculptor is looking at a stone and saying, I see it this way and I will carve it this way. Why winemakers would be resistant to thinking about themselves in that way is fascinating to me.

MS: I’ve thought about this a lot. You laughed at me chasing around California trying to find someone to say that they were an artist as a winemaker. Some of it may be the American views of what it is to be an artist. That it is somewhat elite in some ways, or suggests a kind of egoism about yourself to see yourself that way.

I remember talking with Chris Brockway [of Broc Cellars] and him saying to me, “You know, I have to mop.” And I remember Abe [Schoener, of the Scholium Project] saying, ‘At the very beginning, I was just hoping not to spill a lot of wine on the floor.’ Personally, I don’t see those things as disqualifying them from being artists, though it has to do with their conception of what they do. Abe has moved past that, but Chris hadn’t.

I agree with you, when winemakers can make a wine that is in some way a distinctive expression, and they are trying to do that, that is an artistic gesture on their part.

I tried to test out these theories from literature. They have echoes, certainly in the romanticism element. It’s interesting to me, though, that winemakers resist it. It fits the pattern of what they’re doing, perfectly.

I brought up the classic example of the Aeolian harp, the idea that the artist is someone who gets their inspiration from nature and is then able to produce art through that experience of it. It seems to me that when the rhetoric of winemakers, especially the smaller-scale winemakers I was talking to, is to say, ‘It’s all about the vineyard,’ or ‘It’s all about just simply trying to do right by [the vineyard].’ It’s a resistance to see their role, or celebrate their role. The romantic artist, they are celebrating their role because they are special, because they can be the Aeolian harp.

Maybe it’s a particularly American idea, that [celebrating their role] doesn’t seem right. It’s a paradox, of course, this idea in American culture, the paradox of individualism used as a fulcrum for commercialism. It’s something of that paradox to me. On the other hand, they have to celebrate their role, because, otherwise, why should I buy Ted’s wines over so-and-so’s wines.

“When winemakers can make a wine that is in some way a distinctive expression, and they are trying to do that, that is an artistic gesture on their part.” —Michael Sinowitz

JG: So, one thing that strikes me is that, if this is an American resistance, Cathy Corison is probably one of the most American people making wine in Napa Valley, in terms of being a pragmatist, almost like a Shaker. I’d be curious about your take as to why Cathy is willing to agree to consider her work as an artistic endeavor.

MS: I don’t know that Cathy was expecting to say that to me. Everyone expected Abe [Schoener] to say that to me and people did not expect Cathy to say that to me, and some of that is the fact of the way they present themselves. I was talking with Cathy about her experience—that she’s had an experience that is longer than [that of] a lot of the people I talked to. She had gone through a range of experiences where she had to make a difficult decision about whether or not she was going to continue making wine the way she believed it should be, or change. As a consumer out in the world, you don’t realize how tenuous their lives can be, especially the small-scale winemakers.

I think that, for Cathy, having gone through that and deciding not to change makes her think about herself, and what she did, and why she did it, in a way that, maybe, other people don’t. And I think that’s why she was willing to see what she was doing as a kind of being true to her artistic vision… This is how she wants to make wine; it’s part of how she’s expressing herself. And she wasn’t going to compromise. To me, that’s part of it. But I’m sure that Cathy wasn’t going around and advertising it.

It’s also about the fact that she is just blunt. There’s a way in which the immediate response I was getting [from others] was the thing they had trained themselves to say about what they do. Whereas, by that point in the conversation I was having with Cathy, if she had done that herself, she had left it behind; I thought there was a way in which she was just being direct with me. I think she is largely that way most of the time. It wasn’t what I had expected, but, looking back on it, it makes a certain degree of sense to me. I almost wonder if some of the folks I interviewed—if they are still making wine in ten or fifteen years—might think about what they are doing differently. I felt like the guys at Arnot Roberts were close to admitting it to me. Those guys I think of having really extraordinary aesthetic priorities, it makes sense to me that they would think about what they are doing that way, even though they are both pretty down-to-earth guys. But you can be down to earth and still be an artist.

I feel that is a thing not everyone thinks, that they want to see themselves as down to earth rather than artistic. Some of it is just the rhetoric of how they describe their process, that sort of forbids them from trying to see themselves that way.

Click here to read Joshua Greene’s book review of Finding Meaning in Wine: A US Blend, by Michael Sinowitz.

Joshua Greene is the editor and publisher of Wine & Spirits magazine.

This is a W&S web exclusive. Get access to all of our feature stories by signing up today.