Ed Zimmerman was surprised when I told him that Coche-Dury missed on me. “Huh,” he said. Then he considered the lay of the land in top-fl ight Meursault: “Roulot is loved by sommeliers; Coche is beloved by the wealthy collector; Lafon is more respected by winegrowers and collectors. They are the three standard-bearers.”

It made sense to me, as my taste tends to run with sommeliers, and the complexity of the Roulot Luchets we were drinking over dinner was almost making me cross-eyed.

The wines were all Zimmerman’s choices, a tech-guru’s take on contemporary Meursault. Zimmerman is as much a wine drinker as a collector, having assembled a traveling band of winemakers, musicians, MWs and auctioneers for his visits to Burgundy. Most recently, he was stationed in Meursault with a crowd that included singer-songwriter and fiddler Sara Watkins, who was dining with us tonight at NYC’s Rebelle, and Sarah Jarosz, another “newgrass” virtuoso who was performing at the Bowery Ballroom later that evening.

The restaurant was my choice, based on proximity to the Bowery Ballroom, and the fact that Rebelle, with its exceptional wine program, had just instituted a new program for the wine trade, designed specifically for a dinner like ours. We would bring the wine, they would provide the wine service and menu options that just happened to be unusually well suited to Meursault. It turned out to be well worth investing in the wine service, as sommelier Melissa Morphet had six identical (and beautiful) glasses for each of us, each tagged at the base with the wine name, removing what might be a random variable in perception—glass size and shape— as we set out to compare the wines.

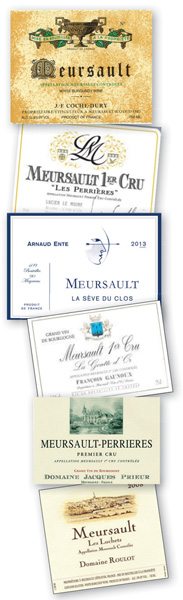

Zimmerman chose first to show two wines from Perrières, the vineyard bordering Puligny that’s being pushed by several growers for elevation to grand cru status. Then Goutte d’Or and Luchets, ending with a lieu-dit and a village wine. Perverse? Perhaps, but the lieu-dit was La Sève du Clos, from centenarian vines tended by Meursault wunderkind Arnaud Ente. And the village wine was made by Ente’s mentor, Jean-François Coche, in 2009.

As an extension of Zimmerman’s “Pledge Against Gender Bias in Tech,” he has insisted that the group be mixed. We were three and three: Christy Canterbury, MW, Denise Barker, the wine director at NYC’s White Street and Sara Watkins on one side of the equation; Richard Young of Christie’s, Zimmerman and me on the other. In fact, with Kimberly Prokoshyn, the wine director of Rebelle, sitting in for the tasting, the bias tilted in a decidedly female direction.

We agreed to taste through the wines in three flights, and then bring on the food, and I asked Zimmerman to introduce his choice of Meursault as a focus, and his selections for the night. “Meursault was out of vogue in the 1990s,” he began, recalling the ups and downs of a village with no grand cru vineyard to append to its name. “There was a program to sell fallow land to young vignerons. Mostly stony, rocky, unusable stuff.

They didn’t have to pay rent for eight years.” Zimmerman hoped to shine a light on the talented young producers in Meursault, plus, as investors often do, he had a hidden agenda. “I do love this village, but there’s an axe I want to grind. There has been a disservice done to the Goutte d’Or vineyard. Historically, it was considered among the top vineyards—it was Jefferson’s favorite, but it has fallen out of vogue.” He hoped to show the standing of Goutte d’Or in the context of two Perrières, as well as to show a range of wines that seem to buck their classification.

“There’s a lower water table in Meursault than in Puligny, so you can have a deep cellar,” Zimmerman said. It’s one element of the local terroir, which might impact the expression of the wines—not only for the condition in which they age. The lower humidity in the soil may be one clue to the richness of the style in the hands of the most talented farmers. As Clive Coates, MW, points out, the yields in Meursault are generally lower, but, he says, “this doesn’t necessarily mean that the wines are more concentrated—there are as many weak ephemeral wines as in the other communes, perhaps more.” Our attending MW, Christy Canterbury, added that “Of all the French styles of chardonnay-based wine, Meursault is the closest to California chardonnay of the 1990s. So it may have gotten dinged for that. It’s easier to see the terroir differences in Puligny and Chassagne because the wines are leaner.”

Lucien Le Moine

2012 Meursault Perrières Domaine Jacques Prieur

2011 Meursault Perrières

We start with Perrières, a vineyard on the slope where Meursault borders Puligny, and Lucien Le Moine, which Zimmerman considers to be a special négociant. He and Watkins had just visited Mounir Saouma in his cellars last month. “Burgundy is kind of xenophobic,” Zimmerman said, “and here’s this Lebanese guy marrying an Israeli cheese maker, buying a stone house in the middle of Beaune, becoming the biggest buyer at the Hospice [de Beaune Auction]. Mounir is a powerful, charismatic guy. His wines have a fingerprint: Made by Mounir. Many people think négociant wine cannot stand at the same level as a grower’s. But Mounir is doing everything in a different way. He leaves the lees in barrels for forever; he ages his whites longer than his reds.”

Watkins recalled how Saouma had them taste his whites after his reds. “He described one of his whites as a red wine made from chardonnay,” she told us. But among his big statements, what struck her was a comment that “Burgundy is not about flavor, it’s about aftertaste.” And the aftertaste in the Perrières was spicy, leesy, hinting at floral notes under the intensity, but overall, closed off. Saouma leaves his wine, untouched, in barrel, to ferment when it will and to interact with its lees of its own accord. As the wines develop a lot of dissolved CO2 during their time in barrel, he insists they should be decanted long before serving. In fact, this wine continued to open over the course of dinner, carrying its grandeur with ease. “Mounir agrees that Meursault is the white wine village in Burgundy,” Zimmerman said. “He loves Perrières and thinks it should be a grand cru.” The power and weight of the wine suggest he may be right.

Like Saouma, Nadine Gublin focuses a lot of her attention on grand cru wines at Domaine Jacques Prieur. Zimmerman, Watkins and their friends had met with Gublin this spring, a visit, he said, that only increased his fascination with the domaine. “Prieur has the greatest string of grand cru vineyards, including parcels of Montrachet and Musigny,” Zimmerman said. “There aren’t many who own both Meursault Perrières and Montrachet. And as far as I can tell, Perrières is a grand cru vineyard in every way, except in the eyes of the AOC. If Meursault were to have a grand cru, this would be it. At thirty hectares, it’s big. Coche-Dury, Comte Lafon and Domaine Roulot all make Perrières, and they are expensive as hell.

“Prieur is based in Meursault, on Rue de Santenots, yet it’s not known as a Meursault house. Nadine Gublin, their chief oenologist, is a complete kickass winemaker. She’s been there for 26 years. But she doesn’t live there, and she’s a hired winemaker, rather than a family member”—unlike the vignerons at the other domaines among Zimmerman’s selections, which, he pointed out, are all locals.

As a collector, Zimmerman has been pondering why Prieur’s wines are undervalued by the market. “If you look at Mugneret Gibourg,” he said of the domaine in Vosne-Romanée, “I don’t believe the winemaking has changed at all from 2002 to 2015. They have gone up four times in price, simply because people have fallen in love with those wines. It’s hard to know why the market recognizes greatness sometimes and not other times.”

Though it presents itself completely differently than the Lucien Le Moine Perrières, the Prieur shares a similar slow pace as it develops in the glass. At first, it’s the only wine that shows its new oak overtly, along with fruit that’s intensely buttery and rich. Then the flavors are long, and, in predicting what will eventually become more expressive, the wine revives in the finish as it shifts into mineral notes.

After Prokoshyn pointed out that the Lucien Le Moine is nutty, Zimmerman recalled a Monty-Pythonesque moment at the Paris airport, when he was interrogated by a tax collector who set out to impugn his purported knowledge of French wine. “What is the marker for Meursault?” the taxman demanded. “Noisettes?” Zimmerman tentatively replied, and the man almost jumped out of his bureaucratic cage to hug him.

Prokoshyn wasn’t getting the hazelnuts on the Prieur, which she found “more linear,” adding, “It’s difficult to distinguish what is the vintage, the vineyard, the producer: what mark you’re picking up on. Overall, I’m picking up on typical Meursault character: creamy; caramelized sugar; a little nutty, brown, toasted quality. At the same time, the tension with the brightness keeps you coming back.” Later, after dinner with a cheese plate, it was the Prieur that had integrated most completely, together with the Comté, lengthening out into a long and subtle finish.

Domaine Roulot

2008 Meursault Les Luchets Domaine François Gaunoux

2008 Meursault 1er Goutte d’Or

“Goutte d’Or is one-sixth the size of Perrières,” Zimmerman said. “It’s much smaller than Meursault’s other premier crus—about five hectares and change, with six vignerons.” But there are plenty of tiny parcels in Burgundy that remain legendary. So why isn’t Goutte d’Or as famous today as it was 200 years ago? “Comte Lafon had a virus in their parcel in the 1990s and had to replant, so they have a young-vine bottling,” Zimmerman suggested as one element of a hypothesis. “And the other producers of Goutte d’Or are not well known. I’m hoping for a reexamination of what’s going on there.”

As for Luchets, “Jean-Marc Roulot told us,” Zimmerman recalled, ‘There’s a reason my Twitter handle is @luchets007.’ He has a full hectare of Luchets,” and the vines date to 1929. Zimmerman chose the 2008 Les Luchets to compare with the Goutte d’Or 2008 from Domaine François Gaunoux.

“For me, 2008 is the magical vintage in white Burgundy,” Zimmerman said. “The 2008s have more acidity and more richness. In the Roulot, it’s more lime. The wine is elegant and pretty. It’s not a rich style. He’s going for an elegant, citrusy style. In the Gaunoux, the wine is richer, weightier.

“One big difference is lees. When I asked Claudine Gaunoux about lees inclusion, she said ‘Never.’ She brought out a magnum of 1970 and poured it into a glass. ‘Do you want to tell my father he didn’t include enough lees?’ The wine was fresh, especially for a 1970. The Gaunoux wines, both red and white, are aged in stainless steel. You don’t see barrels anywhere in the cellar; Claudine got rid of all her barrels in 2000. She does no remontage [pumping over], no bâtonnage [lees stirring], no fining, no filtration. The wines are gorgeous.”

Prokoshyn is another fan of 2008 white Burgundy, defining the wines as “a little muscular, broad and rich, but with an etched quality from the acidity. The wines have retained their freshness. These two are drinking well, still totally beautiful. It’s interesting that Gaunoux is not doing any lees contact; winemakers talk about using healthy lees to preserve the wine from premox [premature oxidation].”

On the other hand, Roulot ferments his wines in wooden vats, then gently stirs the lees every few weeks before malolactic. After that, he racks them into stainless steel on the lees, then ages them in barrel for 11 months, followed by seven months in stainless steel. His 2008 is fresh and brisk, with an aroma I could only describe as the sexiest of the six. Prokoshyn agreed, pointing out the Roulot “is so direct. It has the most electricity.”

As Canterbury pointed out, “There’s a winemaking di erence and a location difference: Goutte d’Or means golden drop, from a sunny spot on the slope. Luchets is a cooler place and should be a little lively.”

And then there’s the personal factor, which may help to explain why the Goutte d’Or is so little known here in the US. “Roulot is a professional actor,” Zimmerman said, “and a fluent Anglophone.” With Gaunoux Zimmerman only speaks French. “She’s always in the vineyard and, also, she’s a mom with small kids, super-devoted to them. She says, ‘I can’t travel around the world and live my life. So if I don’t sell my wine abroad, I don’t sell my wine abroad.’”

Coche-Dury

2009 Meursault Arnaud Ente

2013 Meursault La Sève du Clos

“There’s a theory that even though the Corton Charlemagne of Coche is the most sought-after white Burgundy, it may be an anti-terroir wine because the house style is overly recognizable,” Zimmerman said as we launched into the last flight. “With Coche—and Lucien Le Moine—there’s an extent to which you’re tasting the producer. But if the [Rolling] Stones cover a song, it sounds like the Stones, and I love it.

“Many people said 2009 whites are really bad and won’t last. But I think that’s an extreme view. I like 2009 white Burgundy. This one is expressing a lot of fruit.”

For Canterbury, Coche-Dury is always rich and she found the 2009 vintage accentuates that aspect. “There’s more fruit generosity in this 2009 than in the Roulot 2008,” she said, adding that winemaking style plays a large part: “Coche is more about leesiness—brioche and baguette character—more about how the wines are made and aged.” “Coche is known for a reductive style,” Prokoshyn added, and she was impressed by how direct and fresh it was for a 2009. It certainly held its own among the premier cru wines on the table, as did the Sève du Clos, with an ostensibly humble designation all its own.

“Arnaud Ente is a disciple of Coche,” Zimmerman explained. “His entire domaine is 4.7 hectares, low yields throughout. This wine comes from 100-year-old vines on the flats, near the hospital. Ente used to call it Vieilles Vignes; now it’s La Sève du Clos. In Burgundy, it’s widely agreed that the great terroir was ascertained by the monks. But this wine clearly transcends the terroir; it transcends the village level. Was it a mistake not to make it a premier cru? This wine is expensive as hell and impossible to find.”

Well, not quite impossible. Zimmerman found it at Caves Legrand in Paris, one of the 409 bottles and 90 magnums produced. “Sève is sap,” he said. “The wine should be big and powerful.” And it is—an aspect that’s played up when we begin our dinner: It’s a great match to a plate of raw fluke in brown butter and capers.

But what’s particularly surprising to me is how well the Coche-Dury matches the fluke. It’s a dish that seems to be made for Jean-François Coche’s mineral-rich style of Meursault. I realize that, in the past, I have only ever tasted Coche-Dury without food. And I have to say, in the context of fluke in brown butter, the wine is pretty seductive.

This story was featured in W&S Fall 2016.

illustration by Veronica Collington; map illustration by Vivian Ho

Joshua Greene is the editor and publisher of Wine & Spirits magazine.

This story appears in the print issue of fal 2016.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.