Headed east on the 0-50 from Concepción, we were supposed to turn south at the sign for Yumbel. Manuel Moraga Gutiérrez, whose family has tended a vineyard in town for 300 years, had given us directions. But there was no sign, just a billboard welcoming us to town five miles back. Whatever the 0-50 was last time Moraga had driven it, it was no longer.

So we doubled back and crossed the half-finished highway below the abutments of a half-finished bridge, one of a dozen reconstruction projects that was stopping traffic in one direction while the line of trucks and cars coming the opposite way took their turn on the single open lane. Patricio Tapia was driving. Based in Santiago, he has written about Moraga’s wines in W&S and rated them highly in his annual guide, Descorchados, but he’d never been to the vineyard before. We pulled up at a bus stop where a middle-aged woman was standing, looking like she’d dressed for church, her hair braided and tied back, a hand-woven bag on her arm. When Patricio lowered the window and asked if she knew the way to Yumbel, she slowly shook her head yes. The road for Yumbel was down the highway, I heard her explain in Chilean Spanish. “I’m going there,” she said, so Patricio asked if she wanted a ride.

Our GPS had failed us, but Sonia took us directly to Yumbel, down the torn-apart 0-50 to a new road headed south, then west again into town. She was on her way to meet a magistrate about the water (or lack of water) at her house. After the earthquake of 2010, the government had built her a new house, “very warm, with electricity,” but she still had no water. She thanked us several times before stepping out onto the town square, smiling with a toothless grin, her sunbaked face wrinkling in happy relief to be off the highway.

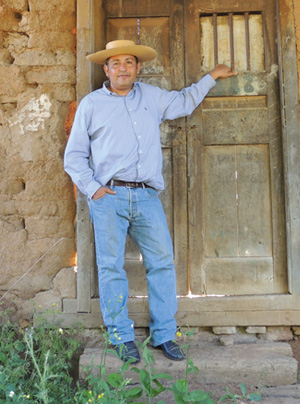

Meanwhile, Moraga and his partner, Paola Marini, had spotted our rental car and came barreling around the square in their late-model Nissan. Moraga shook our hands with the gusto of a man who wears a handlebar mustache. He’s short and stocky, beaming with excited hospitality. Marini is petite, with the bright orange-red hair of a sixties flower child. She works in tourism; he builds houses and works for a dairy in Osorno.

Patricio and I followed their car up a dirt road that leads north out of town, completing the long, wide spiral of our arrival from Concepción.

They parked at the end of a driveway where one new building stood among the ruins of the quake.

Moraga immediately walked us across the road to a hillside of squat bush vines.

“It’s a vein of trumao,” he explained, describing the red volcanic soil from an ancient lava flow that streamed down the hill to the lake below. It’s a narrow belt that doesn’t extend to his neighbor’s vineyard, a light, fluffy soil, running 46 feet deep, easy digging for the rabbits that had built deep warrens among the vines.

His father, a winemaker from Curicó, had planted the top of the hill to cabernet sauvignon, but did not rip out the 40 acres of país that was his mother’s family’s inheritance. His father had trained some of the país to trellises, but left 12 acres as bush vines, and left some of the país vines at the base of the hill to climb to the tops of the oaks and boldos. Marini asked me if I knew boldo, a medicinal plant, as she crushed the leaves in her hands and held them out for me to smell.

Hawks circled overhead, keeping an eye out for the rabbits while we climbed though the low canopy of the vines to the top of the hill. Looking down toward the lake past the tree line, Moraga boasted, “There are no pines here, and no eucalyptus.”

Back across the road, at the fallen winery, Moraga showed us the wood lagar where he had once fermented and aged the wine. There were now plastic tubs outside, along with a new press, pump and hoses in the freshly painted wooden shed. Outside the open door, some friends of theirs had set up a barbecue, and were cooking beef filet over the coals. They were also grilling prieta con país, a wine-infused blood sausage with onions, peppers and cilantro. There was a table set with plates of pistachios and almonds, local cheeses, olives and an array of the wines Moraga produces.

He’s most proud of his Arrope, a sweet reduction of grape juice that’s as orange-red as Marini’s hair. Having a long drive south ahead of me, I declined to taste it.

We cover grapes with vine ashes for a day in our copper alambique, then with a cooking reduction we get Chicha Cocida. If we reduce it again, we have arrope, which is much sweeter and conserves for years. Arrope is like a fine sweet syrup that we use for desserts or to drink a shot after meals.”

—Paola Marini

Instead, I ended up drinking a glass of pipeño, a traditional, low-tech, typically unsulfured wine made and drunk by the locals. I was spitting on the ground now and again in deference to my drive, which would include neither Patricio nor Sonia for navigation. But the fear of getting lost was no match for the delicious freshness of the pipeño, especially with a bite of spicy prieta. There would be no way to taste this at home in the States. Not even in Santiago. This is only here.

If you think of Chileans as Santiago bankers and agribusinessmen, come to Yumbel. Visit these vines that arrived with the Jesuits—listan prieto from the Canary Islands. In Chile it’s called país, a word said with a smirk and a shaking of the head by most of Chile’s winemakers in the north. The most open-minded of those northerners came here and discovered carignan or cinsault, two other old-vine denizens of the Secano Interior—the dry-farmed vineyards of Cauquenes, Itata and Bío-Bío. Locals on the interior side of these coastal hills planted those vines after the earthquake in Chillán in 1939, hoping to boost the color (carignan) and yields (cinsault) of país.

As for país, it’s a bad business, people will tell you. And I was convinced of it until I came here, until I wanted to move here and find a hectare of país, making pipeño and driving into Concepción for a seafood feast whenever the coast beckoned. So now I am no longer an unbiased observer…

Or would I make cinsault? That seemed an equally engaging prospect, standing over a steep hillside of vines, with a view across the coastal range as the sun set over the Pacific 20 miles to the west, the colors in the sky mimicking the mañosa, purple flowers that blanketed the knolls not covered in vines or forest. The mañosa looks magnificent, but it carries a sting, like nettles, as if to remind any visitor why the De Martino family was able to buy this old vineyard in La Leonera (Guarilihue) for a pittance (they paid about $10,000 a hectare—or $4,000 an acre—for 20 hectares of land, including 12 planted to vines, some 100 years old, while vineyard land at their home base in Isla de Maipo typically sells for $80,000 a hectare). But there is no sting when you taste the cinsault rosé Eduardo Jordán and Marcelo Retamal, De Martino’s winemakers, produce from this site. I am not a fan of New World rosé in general, finding most of them too fruity or too sweet, or just clumsy. This one is a pure pink mineral line that lasts through a taste of the Epoisses Jordán had cut open on the tailgate of his truck.

“This place looks like the Langhe hills,” he said. And I could see his point, even though it really didn’t look like anyplace I had ever been in the world. The steep, cascading hills of vines, the untended blocks of what were once vineyard still pushing up through the mañosa and through the forest floor of the pines planted across the dirt track. There is a beauty here that may be dirt poor, but has magnificence. And this wine, in all practicality, is more likely to travel well than unsulfured pipeños.

I had come to the Secano Interior with the impression that there were huge swaths of país, and little difference among them. I left with a clearer understanding of the raw tectonic power of the place, captured in light, refreshing wines like this cinsault rosé and deeper, numinous reds from small blocks of país. After nearly 500 years, the place had developed its own opaque system of crus, kept like family secrets by the people who made them.

Louis-Antoine Luyt explained it best. He has spent the last seven years seeking out these one- and two-hectare plots, ancient vines that each have a connection to the original planting in the 1580s at the Hacienda Cuchacucha, a property now owned by Arauco, the pulp and timber operation that has helped transform this land from vineyards into pine forest.

Luyt had been a sommelier in France when he came to live in Chile. He told me how he had visited vineyards with some enology professors from Santiago and had been intrigued by the history of the vines, but the academics told him they were garbage. So he took some bottles back to France, along with some respected cabernets and carmenères. He had done this tasting first with Chileans, and no one chose the país. When he did the same tasting with friends in France, they all chose the país.

Luyt is a dreamer who is not afraid to get his hands dirty. He’s just as likely as a local farmer to be working at harvest pushing grape bunches through a zaranda, a kind of massive sieve fashioned from bamboo poles tightly lashed together. Placed over a lagar, it provides a mechanism for crushing and partially destemming the grapes.

He settled in Cauquenes, and then most everything he had built was destroyed in the earthquake. As he recalls that night, he woke up under a wall, unable to move for 25 minutes, then when he finally did move, more of the wall fell and pinned him. Neighbors came to save him and he was relieved to find his five month old baby safe. It took a year and a half for him to begin to rebuild; meanwhile, his stepfather and brother created France-Cauquenes, to help raise money for the local hospital and to finance a clinic. His partner in his original project, Clos Ouvert, left, and by necessity, he changed his winemaking approach—“there was just less technology,” he says, as it had all been destroyed. In the end, it led him to focus on what he describes as simple, easy drinking wines.

“Pipeño is a tradition and a culture: the zaranda, open tanks, punching down, and no pressing. People didn’t have money for a press.”

—Louis Antoine Luyt

Luyt told me that the devastation of the quake increased his commitment to paying a fair price for grapes, rather than the depressed market price, as the money became a lifeline for the growers. But even as the region began to recover, he continued to feel like an outsider. Last year he decided to move to Itata, where he found a friendlier community in Bulnes, just north of Yumbel. He set up shop at a friend’s vineyard, with a team, mostly Concepción born, including enologist Roberto Henriquez and agronomist Gustavo Martinez. They plan to harvest 25 individual país sites in the next harvest, up from 14 this year. He produces a collection of “Huasa” wines with carbonic maceration, aged in tank or barrel. His “Pipeños” follow a more traditional method, foot trod in baskets over a zaranda over a lagar. Luyt’s work starts with the farming; his team takes care of the vineyards and then pays a fair-trade price for the grapes, a significant premium over the going rate for bulk país. His economic model separates the great sites, the cooler hillsides, the less humid soils, from the vines that provide generic table wine to the supermarkets in Chile.

He pointed out the vineyards on a map in the cellar as we barrel-tasted through a range of experimental wines—including a sauvignon blanc made in the style of Pierre Overnoy, leesy, beautifully textured, with a through-line of acidity that mirrors a cool Itata afternoon when the sun passes behind the hills and the temperature drops like a stone. There’s the wine he calls his Feiring Cuvée, after wine writer Alice Feiring, who might appreciate a red fermented in the skin of an ox. “The people from the mountains were paid in grapes,” Luyt explained. “To transport the grapes, they used ox skins, so the grapes started to ferment….” And there’s his 2014 La Grand VieDure from the surrounding vineyard, where the carmenère vines are 12 years old. “I really love carmenère,” Luyt said as we tasted it. “I’m going to try to buy some pre-phylloxera carmenère, vines from the 1860s.” Later, Luyt drove me across a long wooden bridge over the Itata River, stopping in the middle to give the lay of the land. It is a very modern idea to plant on alluvial soils, he said, standing over the river’s flood plain.

“País doesn’t like rich soil, and needs soil with less humidity. The challenges are vigor and high yields. And in a warmer place, the acidity goes flat. The cool spots in the Secano Interior are now considered the best land for país.”

—Renán Cancino

Hacienda Cuchacucha was the first place planted here, he explained, pointing toward the hills to the north. “They planted on yellow clay, or red clay, mostly compacted granitic soils.” The hillsides are now forested in pines, the result of a tree-farming program supported by government funds.

“Pines came in the sixties,” Luyt explained.

“That’s when the wine culture started to die. There was overproduction and grape prices were bad. The introduction of pines accelerated into the nineteen seventies and eighties: From south of the Maule River all the way to the Bío-Bío River, people were ripping out natural vegetation and planting pines.

“By the eighties, it was bad taste to drink red wine.” In 1994, when the country redrew the appellation system, the ancient, dry-farmed vineyards of the south got short shrift. “The enologists said Maule was bad for making wine, so the value of grapes went down to nothing. At that moment, people started to drink Coca-Cola instead of wine.

“Pipeños lost their market. All the bottlers had disappeared in the eighties; they all went to bottling beer. When supermarkets arrived, pipeños died. People had changed their way of consumption.”

Back in his truck, we crossed the bridge and headed down a long dirt road that eventually opened up on a settled area with vines. Luyt pulled over and we walked into the farm and the vineyard for his Huasa de Confluencia. He told me the owner’s name but asked that I protect his sources by calling him Carlos. (“Many people are looking for my farmers,” he later wrote to me. “One of them, who is buying grapes from the same farmer [as I am] in Truquilemu, told me my label, Huasa de Trequilemu, was a good idea. It took him two years to find the place.”)

Luyt showed me Carlos’s antique crusher as chickens scattered from the barn, chased into the vines by a screaming rooster. We followed them, finding the shade of a cherry orchard amid the vines, and snacked on cherries as Luyt explained that Carlos is canuto, the Protestant sect in the south of Chile. “He became a canuto because of this wife, and doesn’t drink alcohol.” Luyt recalled the end of the last harvest, when Carlos had said, “Well, because you are here, and because we have worked well together, I think I can have a small glass.”

Luyt described the vineyard as a community of 300-year-old vines, and I found myself wondering about the depth of their roots as I bushwacked through their interlocking tendrils, following the rooster and the chickens up the hillside.

Driving north, past the town of Cauquenes, Patricio told me to turn left at the sign for Sauzal. “It’s about ten kilometers in,” he said, as the pavement turned to gravel and dirt. Twenty kilometers in, we thought we must have missed the turn, and he attempted to make a call on his mobile. I stopped the car to take a video of the wind blowing through a hillside of wheat, the plants in constant motion, as if the wheat had an industry and purpose to its random movements that a human could not see.

Renán Cancino told Patricio that we should keep going. It was, in fact, fifty kilometers down the dirt road to Sauzal, a town on a saddle of land with one central street along the top, gulleys for drainage on either side, somewhat restricting the parking options, and bridges over the gulleys to the side streets. We pulled over at El Viejo Almacén, the old store Cancino’s father had once run in town. Cancino walked us through the original store, now an empty room with posters from a 1950s calendar of bathing beauties, into his barrel room.

He poured us a bright, floral, light-bodied carignan from Flores, which he described as a cool canyon in a warm area surrounded by mountains. And then país from the Moya family vineyard in Truquilemu, a vineyard 22 miles from the coast, a higher spot to the west of Sauzal where the granite soil is thinner. It’s from a vineyard adjacent and just below the vines that produce Luyt’s Huasa de Trequilemu. “The oldest guys in town knew this vineyard,” he said, “and it was really old at the time.”

He carried a bottle of this 2013 Huasa de Sauzal across the street to his house, where his wife and his father were waiting to join us for lunch. His wife served a salad of favas with chopped onion and hardboiled eggs while Cancino poured the wine. A blend from the Moya Vineyard in Truquilemu with another site in Puico, Cancino makes it without any sulfur. It didn’t have to travel far. And it was the most beautiful pipeño I’d tasted yet, a rich red, juicy and clean, as compellingly delicious as a fresh-picked strawberry.

Over lunch, Cancino explained that the core philosophy of the project is to preserve the way people used to make wine in Sauzal. When he was growing up, his father had a lagar next to the store to make wine, but the family didn’t own any land until 1993. Cancino started his career in wine in Concepción, with the likes of Pedro Parra, the noted terroir consultant, and Marcelo Retamal, the winemaker at De Martino. Cancino consulted for De Martino for ten years, and now works as a viticultural consultant for other wineries, including El Principal in Pirque.

Cancino started making his own wine at home in 2008, using modern technology and temperature control. Then the earthquake hit and they had no technology for the 2010 vintage. “The only chance we had to produce wine was as they had in the past, with primitive techniques, without electricity. And we realized the wine was better than what we’d made in previous vintages.”

As it turned out, this 2013 was Cancino’s first commercial vintage of país. Until then, he’d been influenced by his peers and the university professors who told him, “País is shit.”

“But the old guys, the elders in town were asking me, ‘Why don’t you make país?’” He took his first país to his father’s friends and they told him it was too astringent, that país should be a soft, suave wine. “País is sensitive to the soil,” Cancino explained. “It doesn’t like rich soil, and needs soil with less humidity. The challenges are vigor and high yields. And the other problem is that in a warmer place, the acidity goes flat.”

So he focused on the cooler areas of Maule’s Secano Interior, a region he described as “when you’re looking at the Andes from the coastal hills.” Adding that it’s now considered the best land for país. He mentioned Coronel, Piuen, Sauzal, Quenehuao. And Truquilemu, where he has access to five acres of país from Moya.

Perhaps it was the braised cordero with white beans and shoestring fries on top—the best lamb I’ve ever had in Chile, by the way. But his 2013 Huasa de Sauzal tasted like a grand wine of some country I’d never visited before. This was a different Chile. In 25 years of returning to this country, this was a taste I’d never found before: a taste of reality, unencumbered by ego, by winemaker technique or fertile imaginations. It was fruit from vines that know their place.

If you define a great wine as one that travels well, then an unsulfured pipeño is challenged out of the gate. Cancino’s wine is not yet available in the US, but Luyt is making inroads with these wines, and others will follow. This coming year, Luyt plans a release party in San Francisco, where he will bring a cask of pipeño and offer tastes of the wine directly from the cask. He plans to sell his pipeños fresh after the harvest, from June to December of the year in which they were made. From January to May, there would be no pipeños.

It’s a different way of thinking about these fragile wines, and it fits. Give Moraga, Luyt, Retamal, Jordán and Cancino time. The earthquake ripped this place apart, and it set them on a new course.

Joshua Greene is the editor and publisher of Wine & Spirits magazine.

This story appears in the print issue

of February 2015.

Like what you read? Subscribe

today.