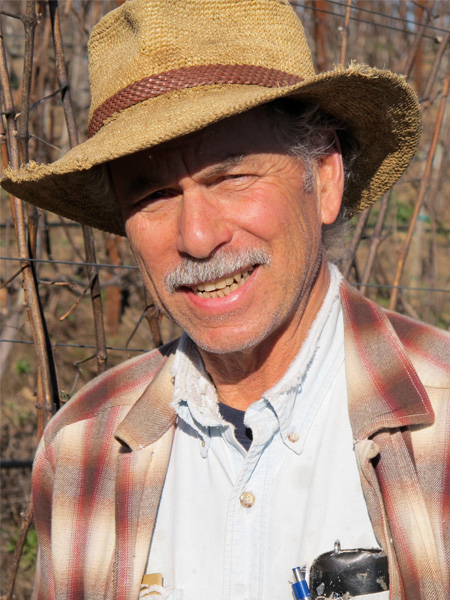

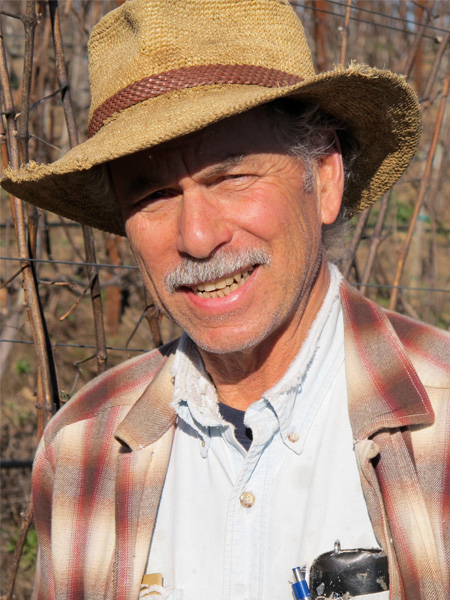

Recently Hirsch came to New York with his wife, Marie, and daughter, Jasmine, to present a retrospective tasting of wines from their family property.

The desolate beauty of Sonoma’s Pacific Coast attracted the Kashia band of the Pomo tribe to…

To read this article and more,

subscribe now.

To continue reading without interruption, subscribe and get unlimited digital access to our web content and wine search.

This is a W&S web exclusive. Get access to all of our feature stories by signing up today.