After his first trip to Burgundy in 1976, Elio Altare took a chainsaw to his father’s botte, making room for barriques. His friend Bartolo Mascarello later responded to the modernists in Barolo with a hand-painted label: “No Barrique No Berlusconi.” These days, all it takes is a handful of visits to Barolo cellars before you begin to ask: Where has the battle between the so-called “modernists” and “traditionalists” gone?

The general feeling in Piemonte is certainly less charged than it used to be—but is this mostly a shift of culture and rhetoric, or is there a quantifiable move toward the center in terms of winemaking and winegrowing practices? We decided to examine what is happening in Barolo winemaking, comparing how winemakers made their wine in 1994 and in 2014. More than 30 respected producers responded to our survey, and we present the results below.Participating Barolo Producers

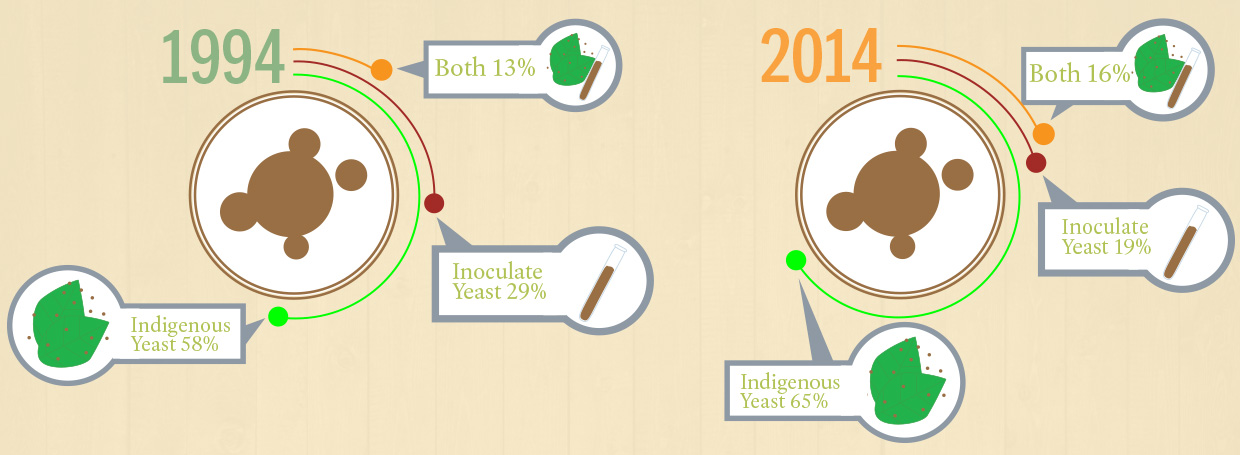

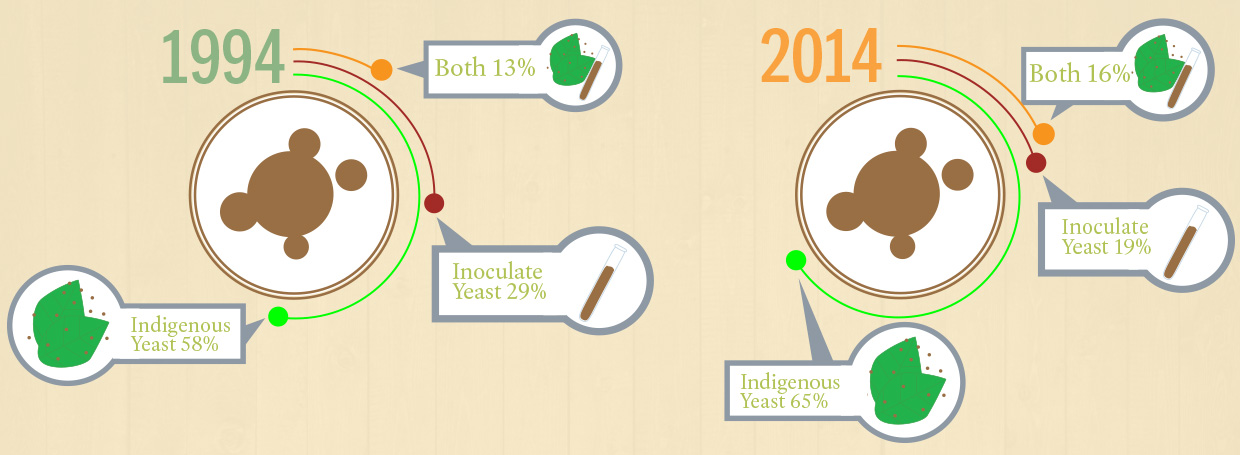

Type of Yeast Used

Our data show a slight shift toward indigenous fermentations, but the majority of Barolo producers have continued to work without commercial yeasts for the past 20 years. Many, like Marco Marengo in La Morra, will start a pied de cuve (a starter culture of indigenous yeasts) from each type of grape right before harvest and then use that to jump-start subsequent fermentations. This mitigates some vinification challenges—potential off odors or stuck fermentations—while maintaining the local yeasts from the vineyard and cellar.

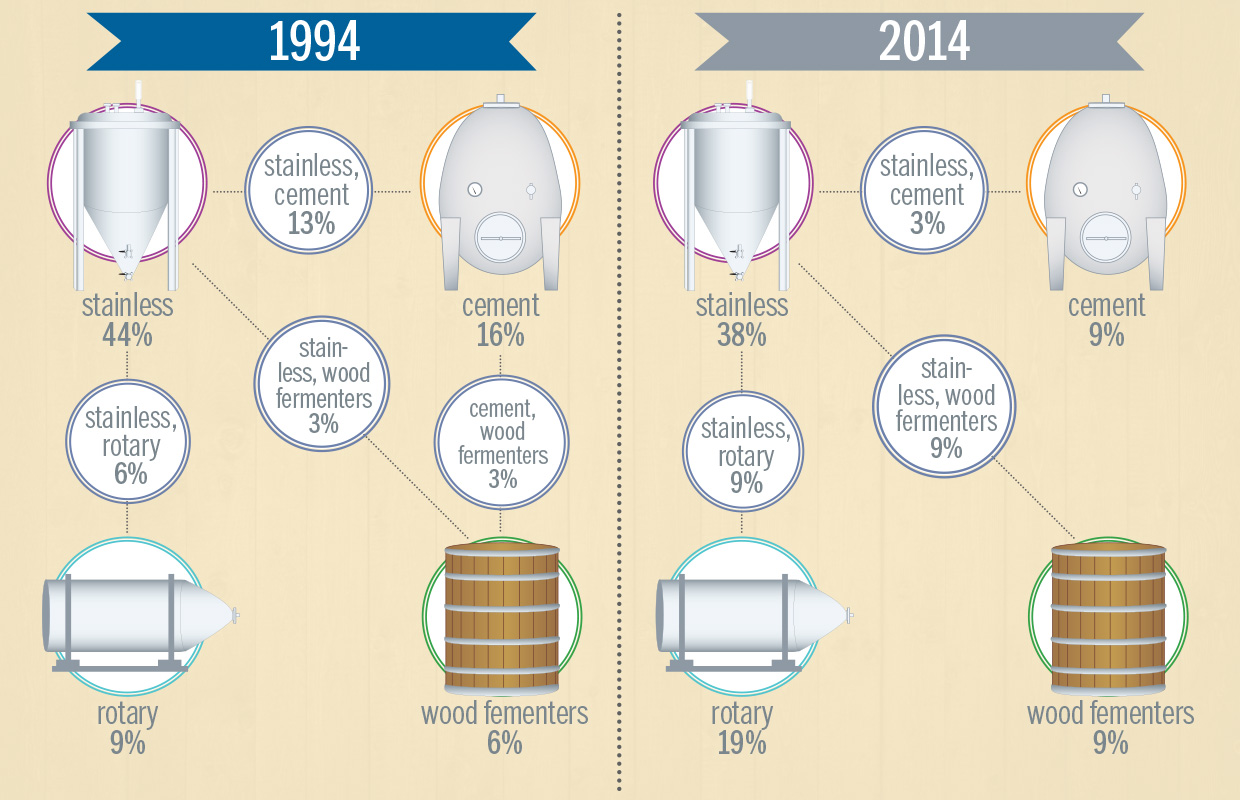

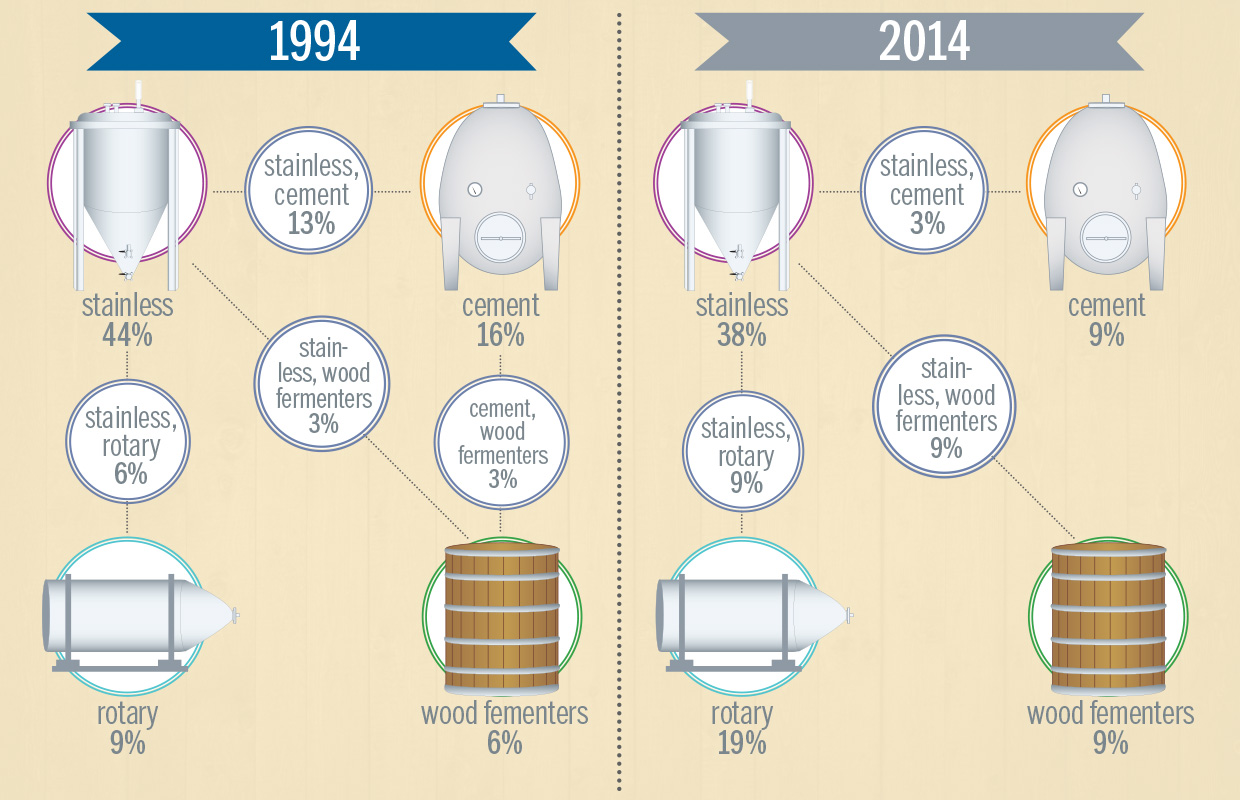

Fermentation Vessels

Starkly “modernist” winemaking implies the use of rotomacerators, short maceration/ fermentation times and French oak barrels for aging. But that is not necessarily how producers are working. In the rotary group, the average maceration and fermentation time is now nearly three weeks, and less than half of those producers subsequently age the wine in barrique alone; most use larger barrels or a mix.

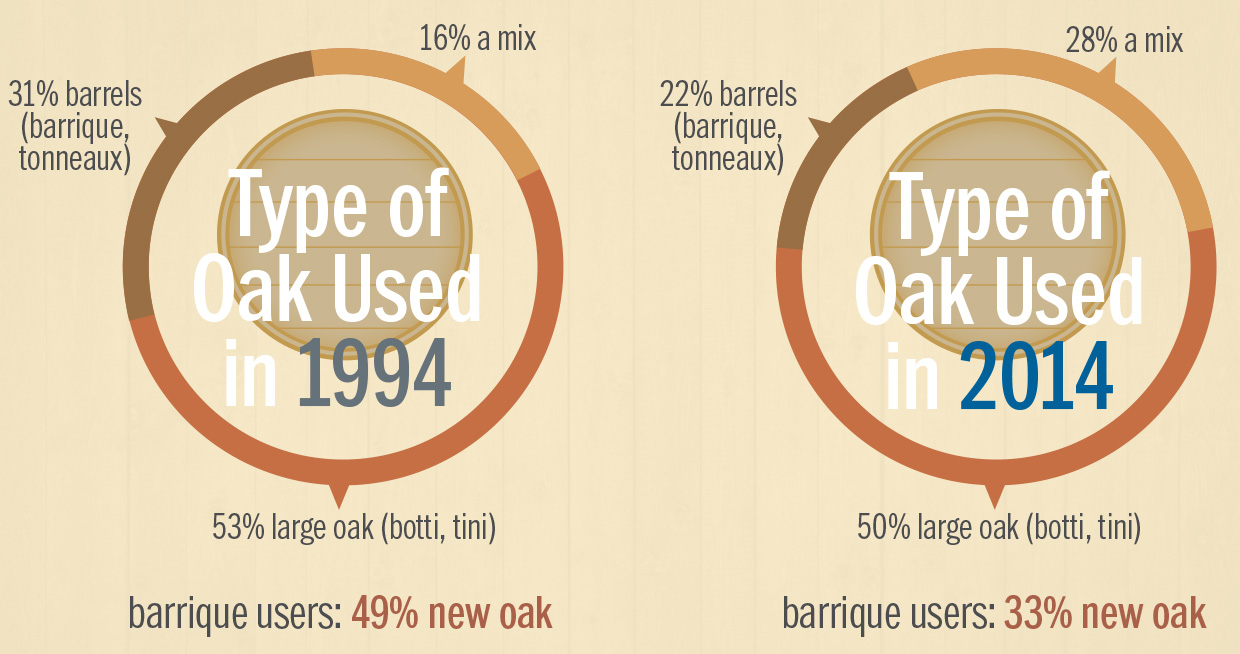

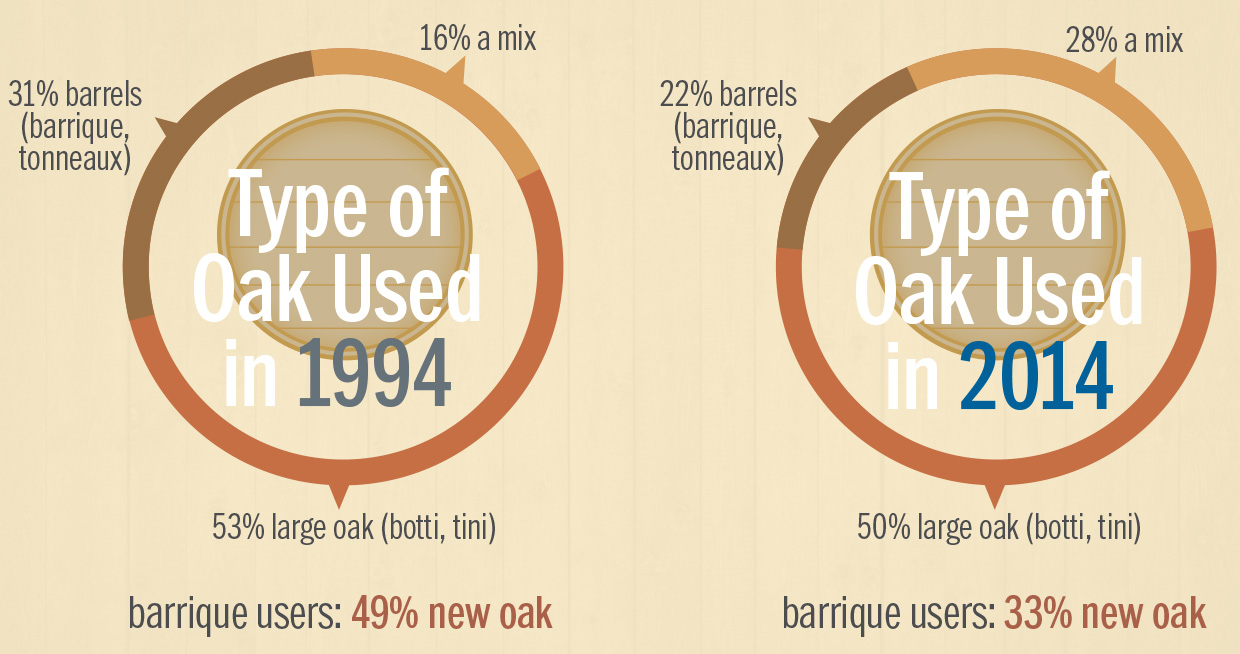

Aging Vessels

Marcella Newhouse is a wine journalist and market researcher living in the Bay Area.

This story appears in the print issue of February 2015.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.