When Steve Edmunds went looking for mourvedre in California vineyards in the mid-1980s, he started to feel like he was pursuing some creature on the verge of extinction. Old growers he tracked down were pulling up “mataro,” as they called it, en masse. It happened so often, he says, that it almost became like a joke. “I’d say, ‘Do you have any mataro?’ and they’d come back with: ‘Oh, I wish you’d called me last October,’ or ‘I tore it out last month’ or ‘last week’ or ‘yesterday.’”

Tempier’s red and rosé became fixtures on the Chez Panisse wine list; the rosé was poured by the glass for the first 30 years of the restaurant’s existence. How could a would-be winemaker like Edmunds, a regular diner at Chez Panisse, not emerge wanting to make mourvedre?

If only he had been seeking out mourvedre in the 1880s, not the 1980s. Referenced as mataro, it was often praised by the experts of the day. In 1884, California chief viticultural officer Charles Wetmore argued that, along with zinfandel, mataro represented the greatest promise for California’s warmer coastal vineyards. Together they’d become “the foundation of our trade in dry red wines,” he wrote in Ampelography of California. “The vine bears well and resists early fall rains; the fruit contains an abundance of tannin; the wine is wholesome, easily fermented, and contributes its fermenting and keeping qualities to others with which it is combined.”

But Prohibition laid waste to this forecast, and by the time Edmunds and others began to seek it out, mataro had all but disappeared from commercial circulation. In 1985, there were 300 acres left, down from 7,000. Most of it was blended into anonymity in jug wines, or sold to home winemakers.

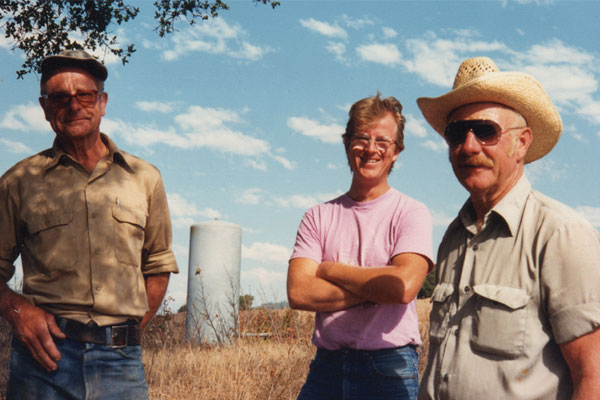

One afternoon in 1985, Edmunds was perusing the bulletin board at the Oak Barrel, a home winemaking shop in Berkeley, and found a listing for sauvignon vert for sale. He called the number, and Richard Brandlin answered. Edmunds told him he wasn’t interested in sauvignon vert, but asked if they were growing any mataro. “‘What do you want with that?’” was the reply. They were, in fact, growing some mataro, and when Edmunds finally got to the property, he found dry-farmed, head-pruned vines that had been planted in the 1920s—zinfandel, mataro, charbono, carignane and a handful of other varieties. Richard and Chester Brandlin had been raised on this land, and with their father had tended it since Prohibition. With a handshake, Edmunds and the Brandlins became partners.

Some years later, in 1987, Kermit Lynch arranged a meeting between Edmunds and François Peyraud, son of Lucien and Lulu, and winemaker at Domaine Tempier. As Edmunds recalls, Peyraud tasted a number of the early Edmunds St. John wines without much comment, and then they came to a barrel containing the first vintage of Brandlin Ranch mourvedre.

“When he got to the mourvedre,” says Edmunds, “he stuck his nose in the glass, and he absolutely just stopped and stood there, for about two minutes. And then very slowly he lowered the glass and his head came up and his eyes rolled back and he took this deep breath and he said, ‘La terre parle,’ the earth speaks.”

Edmunds made wine from Brandlin fruit for the next 12 years; his last vintage was in 1996, when the property was sold, and the contract for the old vines fell to Napa winemaker Peter Franus, who makes a zinfandel from them to this day; he includes what’s left of the mataro, a tiny amount, in the blend.

This story was featured in W&S February 2017.

photo by Cornelia St. John

This story appears in the print issue of February 2017.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.